Outside In: William Heinecke's Big Bet on Thailand

Apr 27, 2016

For a tycoon who makes much of his fortune from grand hotels, spas, exclusive real estate and a fleet of corporate jets, billionaire William Heinecke is surprisingly unfazed by what he acknowledges is a grim global economic outlook. “Luxury does not go out of style during tough times,” says Heinecke, a burly, bearded 66-year-old whose own indulgences include a stable of vintage Ferraris. “In fact, it makes people appreciate it more, although they may demand a little more service for their money.” Service has never been in short supply at his establishments. Heinecke, a naturalised citizen of Thailand born in the United States, owns the Four Seasons, Marriott and St Regis hotels in Thailand and a Radisson in Mozambique. His home is the 8,600-square-foot penthouse atop Bangkok’s St Regis. He is best known as the founder of Anantara, a chain that has become the flagship brand in a portfolio of 145 hotels and 56 spas in 22 countries on five continents.

You’ll find Anantaras and establishments bearing other Heinecke brands such as Tivoli, Avani and Oaks spread around the globe from Brazil to Australasia by way of Europe, Africa, the Middle East, the Maldives, Southeast Asia and China. Though still a relatively new brand – the first hotel was opened in Thailand in 2001 – Anantara was last year ranked sixth among the world’s 25 best large luxury hotel chains by New York consulting firm ReviewPro Guest Intelligence. That put it above longer-established rivals such as the Conrad, Banyan Tree and Ritz-Carlton chains.

Heinecke aims to further burnish Anantara’s reputation. Last year he rebranded the biggest and best known of his four Four Seasons hotels, a stately 33-year-old property on Bangkok’s Rajadamri Road, as the Anantara Siam. He is modernising the teak-furnished, silk-wallpapered rooms and giving guests free smartphones for the duration of their stays. Untouched is the lobby, where Thai and farang businessmen like to wheel and deal beneath the soaring, mandala-frescoed ceiling.

In a recent exclusive interview with #legend, Heinecke rejected any suggestion that he took a risk by declining to renew the contract held by Four Seasons to manage his 354-room flagship establishment. “It has gone through the evolution from Peninsula to Regent to Four Seasons to Anantara, and none of those were a step down,” Heinecke says. “It’s people who make brands, not brands who make people. The location is still the same. The staff are still the same. The food and restaurants haven’t changed.” He concedes with the trace of a smile that the prices are a little higher.

At least every room in the Anantara Siam, including the presidential suite where United States President Barack Obama stayed in 2012, can be booked, which is not necessarily the case at every Heinecke establishment. When he built the Bangkok St Regis in 2011, he topped it with 54 luxury apartments, taking the two-storey penthouse for himself and selling the other residences to buyers he approved of in person. Fortunately for #legend readers, Heinecke, who lived in Hong Kong for four years as a child, has no bias against its people, several of whom were allowed to buy. “There isn’t one owner I wouldn’t be happy to have dinner with,” he says. “They are friends, very illustrious, very elite. We don’t use agents or brokers.” Heinecke is applying the same criterion in selling exclusive real estate he is developing on Phuket.

On a hillside above the sumptuously appointed Anantara Layan Phuket Resort on an otherwise undeveloped stretch of the island’s west coast, Heinecke is building 15 villas, which are going for between HK$55 million and HK$110 million each. That outlay affords buyers a building of mansion-like proportions containing up to 22,000 square feet of floor space, three to eight bedrooms and quarters for a live-in butler. The villas will fuse Thai and Western styles. Each will have a 20-metre-long infinity pool and perfect views of sunsets over the Andaman Sea. The owners will be able to dine in the resort’s restaurants and use its other facilities. Additional facilities include a luxury spa, a 27-metre Sunseeker yacht and a Muay Thai boxing ring, where an instructor wearing a deceptive smile will await those as athletically combative as they are rich.

Villa owners too status-conscious, discreet or short of time to take a commercial flight to Phuket can charter an aircraft from Heinecke’s MJets company at Bangkok’s Don Muang Airport. The company will also take care of aircraft belonging to residents. The planes in the MJets fleet range from an 18-seat Gulfstream GV to a six-seat Cessna Citation CJ3. For beachgoers in a hurry, the fleet includes a Mach .92 Cessna Citation X, one of the world’s fastest business jets. For those that live life too fast for their own good, the squadron includes an air ambulance. At the time #legend spoke to him, Heinecke had sold three of the Layan residences – at least one of them to a Hong Kong buyer. He was expecting to sell the rest by the end of next year.

Heinecke also offers well-heeled tourists and business visitors a matchless opportunity to savour his billionaire lifestyle. Money alone may be insufficient to buy you one of the dwellings Heinecke has built in Bangkok and Phuket, but he is not averse to making an extra dollar by letting his own St Regis penthouse when he’s not using it – which is quite often, because he also keeps a house in the suburbs of Bangkok. For about HK$55,000 a night you can sleep in his bed wrapped in 300-thread-count linen; gaze at memorabilia that includes the costume worn by Yul Brynner in the Broadway production of The King and I; marvel at the Jim Thompson silk murals, Benjarong porcelain and the marble spiral staircase; have a massage in the private health and fitness room, watch videos in his home theatre, wallow in his infinity pool; be served by two bow-tied butlers at his 16-place dining table; and gawk at the astonishing, nearly all-round views of Bangkok from the terrace or through the two-storey-tall windows. If you think the best views of Bangkok are from a riverside hotel such as the Mandarin Oriental, renting Heinecke’s penthouse, gives an entirely different – and broader – perspective of the great city. Although Heinecke’s enviably stocked wine cellar and cigar humidor remain under lock and key for the duration of your stay, you’re free to order from his eclectic collections.

If Heinecke’s bet on luxury sounds optimistic, given the state of the global economy, bear in mind that he has a record of making money amid crises that have ranged from economic crashes to natural disasters and political upheavals. Remarkably, he made his fortune in Thailand. Many Chinese brought to Thailand by their nation’s diaspora have prospered, but some Westerners have found the Thai business climate too sticky – especially those, such as Heinecke, that speak little of the language. Heinecke made his first big bet on the Land of Smiles when he was a teenager. Heinecke is the son of a US diplomat who was posted to Thailand during the Vietnam War. He studied at the International School of Bangkok, but resisted parental pressure to return to the US to continue his education at Georgetown University. Instead, at the age of 17, he borrowed US$1,200 to set up an office-cleaning business in Bangkok, naming his company Minor Group to reflect his juvenile status. From there, Heinecke branched out into advertising and fast food, and in 1976 struck a deal with the manager of King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s private property, Usni Pramoj, to open his first hotel on land belonging to the king in the resort of Pattaya.

In that era there were not unfounded fears that Thailand would be the next Southeast Asian domino to fall to communism after Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. But Heinecke had no doubts about Thailand’s prospects and Usni had no doubts about Heinecke. Usni says the American struck him as totally honest. It was the start of a long and profitable relationship for both men. Heinecke’s two main hotels in Bangkok, the Anantara Siam and St Regis, are built on the king’s land. The king and members of his family hold shares in Heinecke’s business, now called Minor International Pcl. Since 2000 the price of Minor shares has outperformed the Stock Exchange of Thailand index, rising at an average annual rate of 37 per cent. Last month its market capitalisation was US$4.5 billion. Heinecke owns 34 per cent, making his stake at least US$1.5 billion. The royal family’s stake of 4 per cent is worth US$180 million. Last year Minor’s net profit rose by 15 per cent to 3.67 billion baht on revenue of 24.3 billion baht.

Heinecke made what was perhaps his biggest bet on Thailand in 1991 when he renounced his US citizenship to become a Thai. His US-born wife and childhood sweetheart, Kathleen, did the same. They now need visas to return to the land of their birth. At first, Heinecke found doing business in his adopted country deceptively easy. He built hotels and snapped up franchises to sell Western fast food, including the Pizza Hut, Swensen’s and Dairy Queen licences, and he expanded the chains rapidly. But in 1997 the baht collapsed, unleashing the Asian financial crisis. As the value of the currency plunged to 55 baht to the US dollar from 25 baht, hundreds of entrepreneurs that had borrowed in US dollars found their business empires bankrupted. Heinecke says his business survived only because he sold almost every available asset he owned abroad that he could get hard currency for, including a Jaguar E-type and a Chevrolet Corvette, and spending the proceeds on propping up his business. Within two years, Minor was profitable again and Heinecke was in a strong enough position to mount two of his most audacious business coups against US rivals.

Investment bank Goldman Sachs made a hostile, US$46-million bid to take over the Bangkok hotel then called the Regent, the Anantara Siam, in 1999. Heinecke, who owned 25 per cent of the hotel’s stock, made a counter-bid that was less financially attractive but won the support of minority shareholders, including the managers of the royal purse. Goldman Sachs ended up with just 41 per cent of the stock and eventually sold to Heinecke for US$19 million. Anil Thadani, an investor in Heinecke’s companies, said later that Heinecke had succeeded by persuading other shareholders that the hotel was a sacred Thai asset that must never be allowed to fall into foreign hands. “Goldman’s offer was higher but Bill’s public relations machine was better,” Thadani said.

Heinecke then had to do battle with the world’s second-biggest operator of fast-food restaurants, Tricon Global Restaurants, since renamed Yum! Brands. As owner of the Pizza Hut chain, Tricon demanded that Heinecke increase the royalties he paid for the Thai franchise by half and refrain from operating restaurants on behalf of other fast-food chains. Heinecke promptly relinquished his Pizza Hut licence and launched his own brand, The Pizza Company. Today, Thais devour far more of Heinecke’s pizzas than the US brand. Since winning the pizza war, Heinecke has launched other restaurant chains in Thailand, ranging from Burger King to Coffee Club. He acquired Coffee Club from its Australian founders and introduced it in a diverse range of countries, including China and Egypt. Heinecke is also involved in retailing, owning the rights to sell Gap, Bossini, Esprit, Charles & Keith and Banana Republic in Thailand.

Heinecke has had to face challenges other than those posed by business rivals. In five decades of doing business in politically volatile Thailand, he has lived through six military coups, a demonstration that closed Bangkok’s airports at the height ofHeinecke’s most recent problem was the bomb attack on Bangkok’s Erawan Shrine, which killed 20 people. The shrine is a five-minute walk from the Anantara Siam and St Regis. The number of tourists visiting Thailand dropped, but soon rebounded – recovering from the latest setback just as it recovered from previous setbacks. “It was pretty quiet for a little while,” Heinecke says. “But people have short memories. These things can happen anywhere in the world and in many cases they have happened.”

Heinecke loses little sleep over the turbulence in Thailand’s recent history. “A lot of people spend a lot of time worrying about what’s going to happen in Thailand, the political situation and things, but I try not to because there’s nothing I can do about it,” he says. “We just stick to our knitting and stay focused on our hotels, food and retail.” Heinecke attributes Anantara’s global success in part to Thai culture. “One of the things that Thailand is world-class at is hospitality,” he says. “You have some of the finest hotels in the world here in Bangkok and one of the elements of Anantara is its Thai roots.” Outside Thailand, the Anantara chain assumes, chameleon-like, the hue of Thai culture, whether in the Maldives or the Middle East. “Unlike other international hotels, you don’t wake up in the morning and wonder which country you are in,” he says.

Despite his faith in Thailand, Heinecke decided years ago to hedge his bets by diversifying beyond the kingdom’s borders – if only because there’s a limit to the number of opportunities he hasn’t already taken in his adopted country. Nowadays almost half his revenue comes from outside Thailand, including a big stream from the Coffee Club and the Oaks chain of resorts and serviced apartments in Australia.

So far, Heinecke has had less success in China. Today, China still only has one Anantara, the Anantara Emei resort at the foot of Mount Emei, a mountain sacred to Buddhists and a UNESCO World Heritage site. He also operates fast-food restaurants in China and for the past two years has made a small profit there. Heinecke has plans to take his Oaks brand there. “It is a long-term opportunity,” he says. He has made no investment in Hong Kong, although he does not rule out the possibility. “It is not an easy market with rents so expensive,” he says. But he had the same reservation about Singapore, which eventually proved to be a successful market for his fast-food chains.

Anyway, Heinecke makes plenty from the surge in the number of Chinese holidaying abroad. He values their business. “People tend to think China is low-end, but it really isn’t,” he says. “You will find a lot of Chinese guests in our hotels, in places like Phuket and the Maldives, and they are not paying a special low price. They are paying the same price as everyone else. A lot of money has been made in China.”

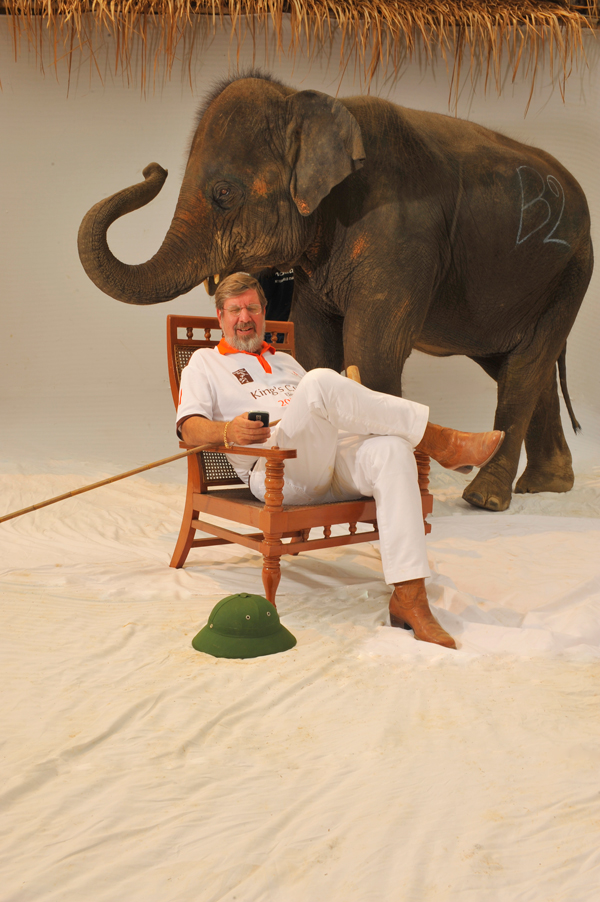

When he’s not making money for himself, Heinecke uses his entrepreneurial nous to raise funds for Thailand’s beleaguered population of elephants. In that endeavour, too, he has been spectacularly successful. The annual elephant polo tournament he stages has become Thailand’s smaller equivalent of the Hong Kong Rugby Sevens, attracting international competitors and fans. Heinecke also founded an elephant camp in northern Thailand which has become an attraction drawing visitors to two of his resorts, the Four Seasons Tented Camp Golden Triangle and the Anantara Golden Triangle. Heinecke’s camp and charitable foundation gets elephants off the streets of Bangkok and other Thai cities, and provides work for the animals, their mahouts and the families of the mahouts. One of the cottage industries the families are engaged in is making paper from elephant dung.

What will happen to Heinecke’s business and his philanthropic endeavours if he leaves the scene? Neither investors nor the elephants need worry, he thinks. First, he has no plans to retire. Should he fall under a pachyderm’s feet, there’s a succession plan in place to keep Minor humming. One of his two sons, John Heinecke, runs the food business, and professional managers run the hotel empire. Even so, Heinecke senior will be a hard act to follow. Business rivals, franchisees and investors say he is as tough and uncompromising as he is smart, especially when cutting deals. Heinecke prefers to describe himself as competitive, “giving people a hard time, getting them to perform to get the best out of them”.

Heinecke stresses the importance of willingness to learn from competitors. He has no plans to rebrand as Anantaras his hotels that are part of the Four Seasons, Marriott, St Regis or Radisson chains. “It gives us a great opportunity to measure ourselves against those great companies,” he says. “As a way of benchmarking ourselves we are in a better position than our competitors, who don’t have that window on the world.” How has the Four Seasons chain reacted to him taking away its biggest hotel in Thailand? Heinecke says Four Seasons has caused no problems. “I still own three others, so they had better be nice to me,” he says.

In his private life, Heinecke is rather an enigma. He enjoys his penthouse, wine cellar, fast cars and executive jets, but in other ways he is remarkably low-key. He is not a flashy dresser, has been married to Kathleen for 48 years, moves around Bangkok without a retinue of hangers-on and has no aversion to flying on low-cost airlines. At the end of a recent business trip to Phuket with members of his executive team, the company jet was too small to take them all back to Bangkok. His staff needed to return before he did, prompting Heinecke to give up his own seat on the plane and fly home on Air Asia. “It was the logical thing to do,” he says.