Remembering I. M. Pei's influence on architecture

Oct 07, 2024

The first full-scale retrospective of one of the greatest architects of our time, M+’s I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture offers a grand tour of some of the world’s most iconic buildings. Co-curator Shirley Surya talks to Jaz Kong about Pei’s enduring – and undeniable – influence

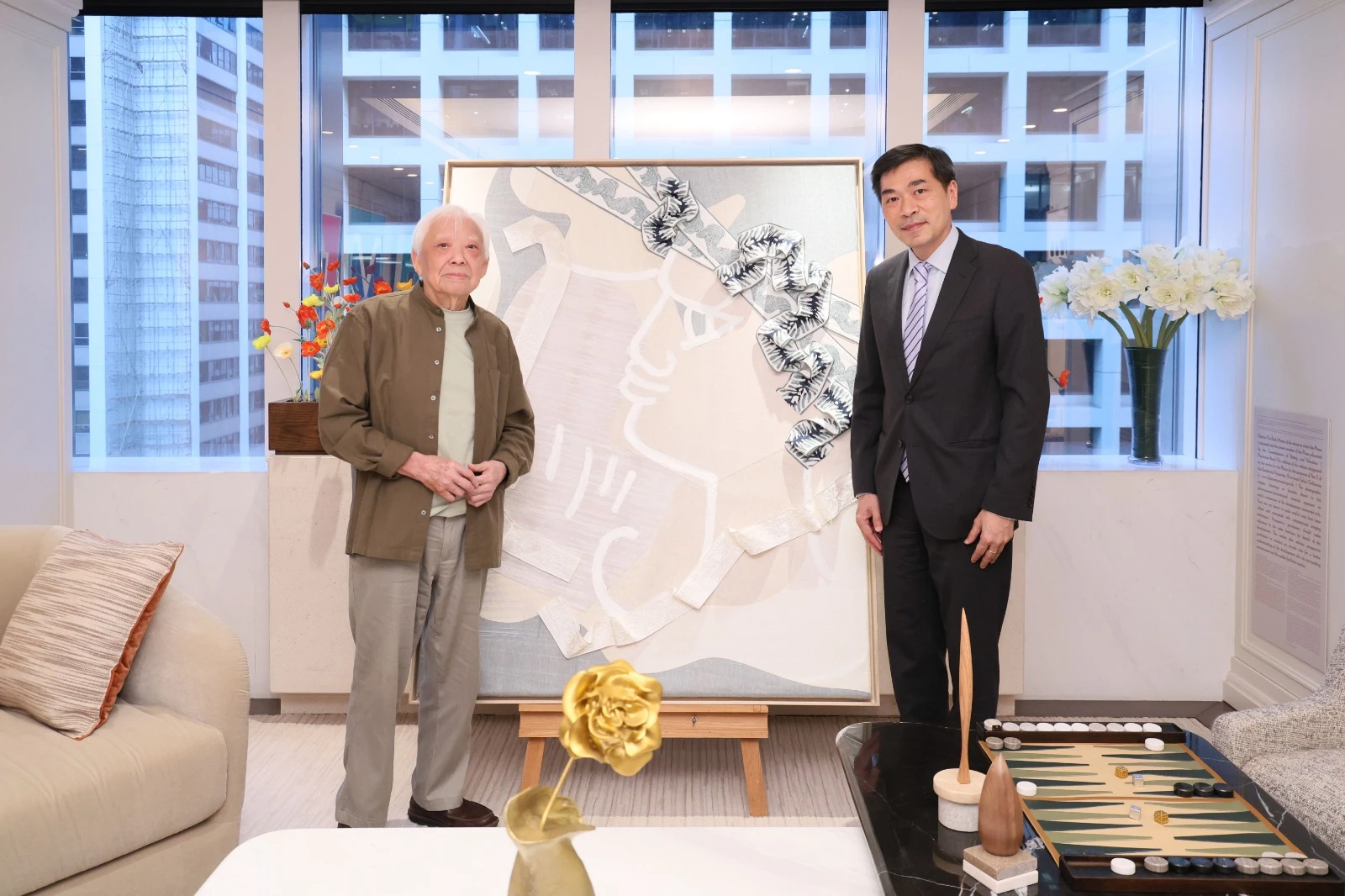

What do you admire most about I. M. Pei? His architectural works? His magic touch with materials? His ability to break through cultural barriers? The Pritzker Prize winner’s talents are certainly unparalleled, and M+’s special exhibition, I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, stands in testament to that fact. But Pei’s son Sandi, who together with his brother Didi co-founded PEI Architects in 1990, perhaps says it best: “My dad is a humanist first, architect second.”

Born in Guangzhou in 1917, Ieoh Ming Pei grew up in Hong Kong and Shanghai before studying at MIT and Harvard, and eventually becoming one of the greatest architects of the 20th and 21st centuries. While he designed dozens of remarkable buildings over his 70- year career, Pei is best known for such high-profile projects as the National Gallery of Art East Building in Washington, DC, the modernisation of the Louvre in Paris, the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha.

Besides the Pritzker – whose US$100,000 award Pei used to create a scholarship fund for Chinese students to study architecture in the US provided they return to China to work – his long list of honours includes the Gold Medal for Architecture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the first Praemium Imperiale for Architecture from the Japan Art Association, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Henry C. Turner Prize for Innovation in Construction Technology and the US Presidential Medal of Freedom.

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, which runs until January 5, 2025 in M+’s West Gallery, is not only an affirmation of Pei’s position in architectural history and popular culture but also the first full-scale retrospective of his life and work. The fact that it is being presented in Hong Kong speaks to Pei’s local influence and history – in particular the iconic Bank of China Tower (1982–1989) that can be seen across the harbour from M+ – as well as the city’s position on the global stage.

“Hong Kong is perfect for addressing the different geographies and Pei’s role in developing them because we touch both Southeast Asia and Greater China, but also we’re related to what’s happening in Europe and the US. It’s quite a privilege but also a choice for us to host this,” says Shirley Surya, M+’s curator for design and architecture, and co-curator of the exhibition. “There’s also the fact that he lived here for about 10 years as a child and all his good friends were here. And when we saw the letters between him and his father, they were all related to Hong Kong. Even towards the late part of his life when he couldn’t travel anymore, he still wanted to come back. This is where he would transit all the time for food, for sweets, for making his suits.”

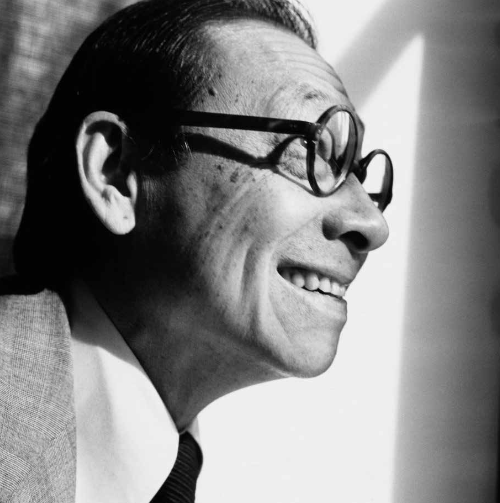

While Pei might not have a particular design style, he is very much recognisable by the round glasses that sat right above his cheek – and that welcome visitors as they enter I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture. The exhibition is divided into six themes, starting with “Pei’s Cross- Cultural Foundations” summarising his family, his upbringing and his studies in the US. (Take a moment to admire Pei’s beautiful penmanship, as seen in his letters to his father and friends.) Moving on, “Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment” details his early success after graduation, while “Art and Civic Form”, “Power, Politics and Patronage”, “Material and Structural Innovation” and “Reinterpreting History through Design” explore Pei’s high-profile architectural projects that are in dialogue with social, cultural and biographical trajectories.

Surya and co-curator Aric Chen spent thousands of hours going through never-before-seen materials from the archives of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and the Library of Congress, as well as Pei’s family, clients and collaborators. Sadly, Pei passed away in 2019 at the age of 102 during the early stages of the exhibition’s preparation, which only fuelled the team to dig deeper and push more boundaries.

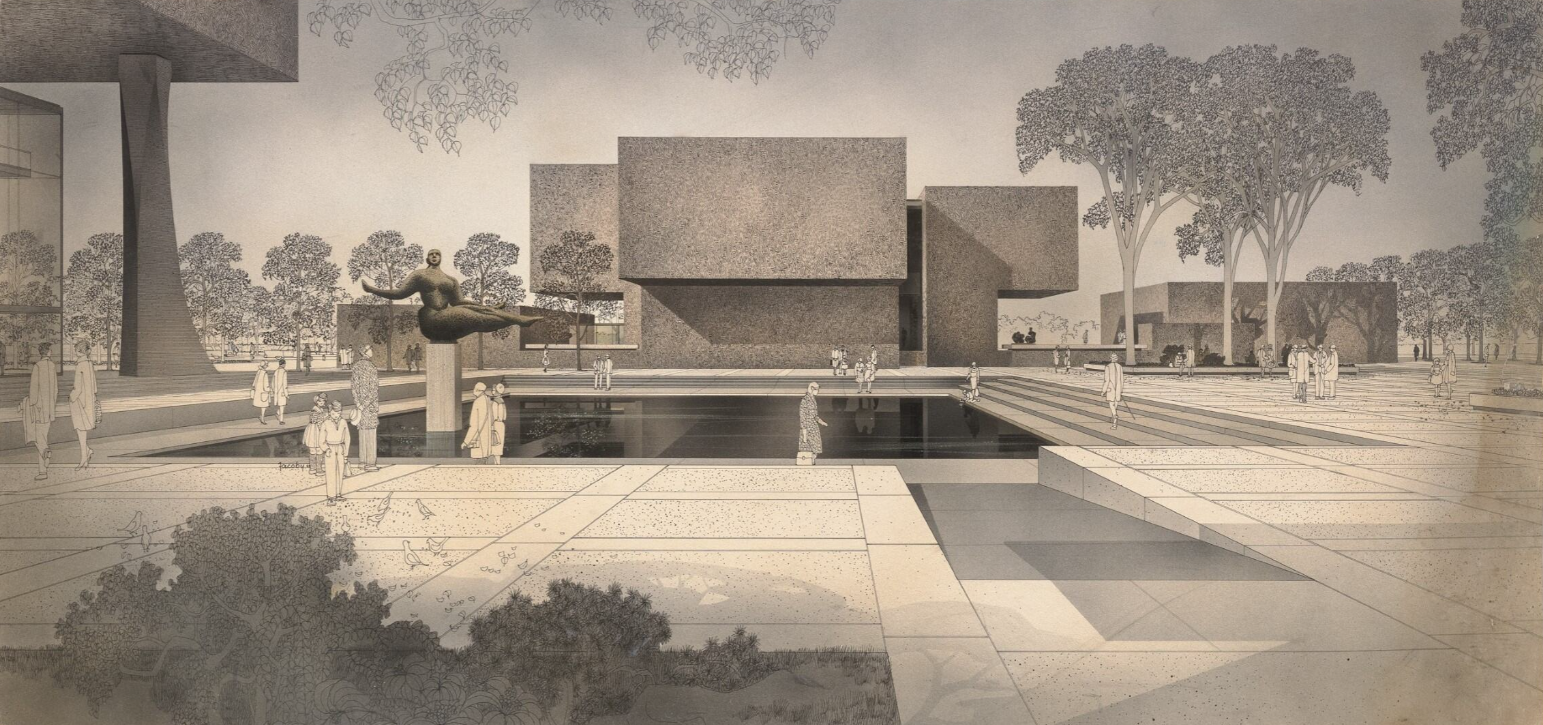

Pei is deemed one of the most inventive architects of all time, partly because of his play with materials. When visiting some of his buildings in person, Surya was surprised by what she came across. “Each project was a revelation to me,” she says. “For example, the Everson Museum of Art [in Syracuse, New York], which was his first museum, is an example of how he dealt with concrete, a ‘dead’ material, and turned it into something poetic. Through a special treatment, the building reveals light and shadow and the passing of time. Time actually moves as the sun does!”

Surya believes this explains why architecture matters and why buildings are not just standalone structures but part of a bigger picture. “I don’t call Pei a particular style of architect. He was just so sensitive to every project’s condition, whether the site, the environment or how people used it,” she says.

Adapting his own take on modern architecture philosophy, Pei believed that form follows intention, which includes function. “He was not an artist per se, but he was very aware of the power of form and the power of moving through space,” Surya explains. “The space-frame-like roofs that were made from joints for Suzhou Museum, Miho Museum or even the Louvre are some great examples.”

Architecture, however, does not exist only to serve an elite few – a fact that Pei illustrated through such projects as the Kips Bay Plaza low-cost housing complex in Manhattan. “When we were visiting, some residents told us that they had been living there for 30 years. And they just attest to how thriving the neighbourhood is,” Surya says. “It’s a beautiful project, but also very civic – I use the word civic because it’s really more about the building than simply the object, it has to do with the entire surroundings. He even negotiated for the use of the land.”

“Let there be light” is the best way to describe Pei’s museum designs, in which he was one of the pioneers in “opening” rooftops and letting the natural light come through. “Of course it’s not a very hot light,” Surya notes. “He managed to put water on the roof so that it reduces the heat. So there are these things as well that are great techniques.”

Another movement Pei started is “the publicness of museums”. Take the National Gallery of Art East Building (1968–1978) in Washington, DC, as an example: “The evolution of museum design with the concept of the public square within a museum did not gain popularity until a few years later. And one of the most humanist quotes Pei mentioned in the documentary about the National Gallery of Art was that he wanted it ‘to be a place to be’. It’s not just a place [for art] but also where people can hang out, where you can choose to look at the artwork or just be around people. It’s a simple statement, but to achieve it is not easy.”

Pei had already risen the ranks of global architecture when he took on the Grand Louvre project (1983–1993), but it took Parisians years to warm to his efforts to modernise and expand the former royal palace – especially the centrally located glass pyramid that would form the new main entrance to the museum. In the end, the Louvre (and Paris) embraced Pei’s glass atrium roof, his sense of community and openness, and his belief in the dialogue between art and architecture.

However, with a little digging, Surya found a lesser- known fun fact about this project. “He realised that tour buses used to be all parked at Rue de Rivoli, which is the main avenue on the right [of the Louvre]. And it created a huge amount of traffic,” she says. “So Pei actually made sure there’s a parking lot where all the buses can go and not block the road. So all these urban elements are things we didn’t know about. It’s really more than just a museum, it’s the whole area and how people get to it. I think it’s very eye-opening.”

As someone who has admired him for a long time, Surya is certain that Pei’s true power lies within, given what he has endured culturally, politically and historically. His career was marked by technical mastery and ingenious problem solving, but also persistence in engaging with powerful clients and politics. One might be surprised by his involvement in the Miho Museum [in Japan’s Shiga Prefecture southeast of Kyoto], especially during a period of strong anti-Japanese sentiment.

“Think about it while he was studying abroad, his home was probably being bombed. Of course he felt something, but I think he was able to see through it and just see Miho as a project and not have any bias. He was able to strike a balance,” Surya says. Not only that, his early days studying and working in the US took place before the civil rights movement called for an end to racial segregation and discrimination. How did Pei manage? However he did, nobody made any comments. But that’s why Pei is a great example. He didn’t oppose engaging with different people. He still spoke for his people, but without squashing others.

Pei’s buildings are somewhat eternal (even though Sunning Plaza in Causeway Bay was torn down for redevelopment in 2013) and indeed have a sense of timelessness. What Surya hopes for visitors to realise from this retrospective is not whether Pei was a trendsetter, but that his incredible talent and transcultural vision laid a foundation for the world we live in today.

Also see: Balenciaga celebrates European Heritage Days with exhibition of Timeless Craftsmanship