Raising the barre: How 'Jewels' inspired Van Cleef & Arpels’ ballet collection

Jun 18, 2021

Balanchine répétiteur Diana White gives a master class on the occasion of the Hong Kong Ballet’s production of Jewels, presented by Van Cleef & Arpels. Zaneta Cheng gets in step to learn more about the American choreographer and his uniquely expressive style

When George Balanchine was artistic director of the New York City Ballet, a role he occupied for more than 35 years at the company he co-founded with Lincoln Kirstein, the father of American ballet was a stickler for tendus in the company’s daily morning class. Diana White, once a dancer in the New York City Ballet under Balanchine and now a Balanchine répétiteur, recalls having to do upwards of 50 repetitions of the very basic step – which involves dancers extending their leg straight out to a point in front, behind or to the side, and then drawing their legs back to the starting position – at the barre to a progressively faster tempo.

It’s one of the most basic steps in ballet. Four-year-olds are taught it in beginner classes. But the step is foundational and White explains that “Mr B”, as she and other dancers in the company called him, was adamant about having perfect foundational technique regardless of the way he would bend rules in his signature neoclassical style.

In a masterclass White teaches on the occasion of the Hong Kong Ballet’s three-night performance of Jewels, a ballet choreographed by Balanchine, she replicates the exercise for students and introduces the concept of irregular beats the way Mr B once did with White and her cohort of dancers. Five tendus to the front, one to the side, two to the back, and those who are trained to dance begin to get a sense that Balanchine really didn’t look to produce a classical ballet style.

“The creation of the ballet Jewels is a milestone in the history of classical dance and was really the first time that such a creation was based on the friendship of a choreographer and a jeweller”

Nicolas Luchsinger

“In Jewels, each section has a specific flavour. Mr B didn’t come into the studio with a set idea in his brain of what he wanted to see. He came into the studio to work with music that he loved and dancers that he knew and appreciated,” White says during class. “He was very particular, the way he chose dancers to be in his company, because he said it wasn’t just the people with the perfect body and perfect feet. It had to do with the dancers’ talent, their musicality, their movement and their desire. He once said, ‘I don’t want dancers who like to dance, I want dancers who have to dance.’

“When I was in the New York City Ballet, there were a hundred dancers at the time and each one of those had been chosen by Mr Balanchine, mostly out of the School of American Ballet. But most of the dancers in the School of American Ballet came from all over the place, so he had a really diverse company. We didn’t do ballets like La Bayadère, for example, where you’d have a corps de ballet where all the dancers kind of look alike and have to dance the same. It was very much the opposite of that. We had all types, all nationalities, all colours in the company. So when he made Jewels, he was inspired by the dancers he had to work with.”

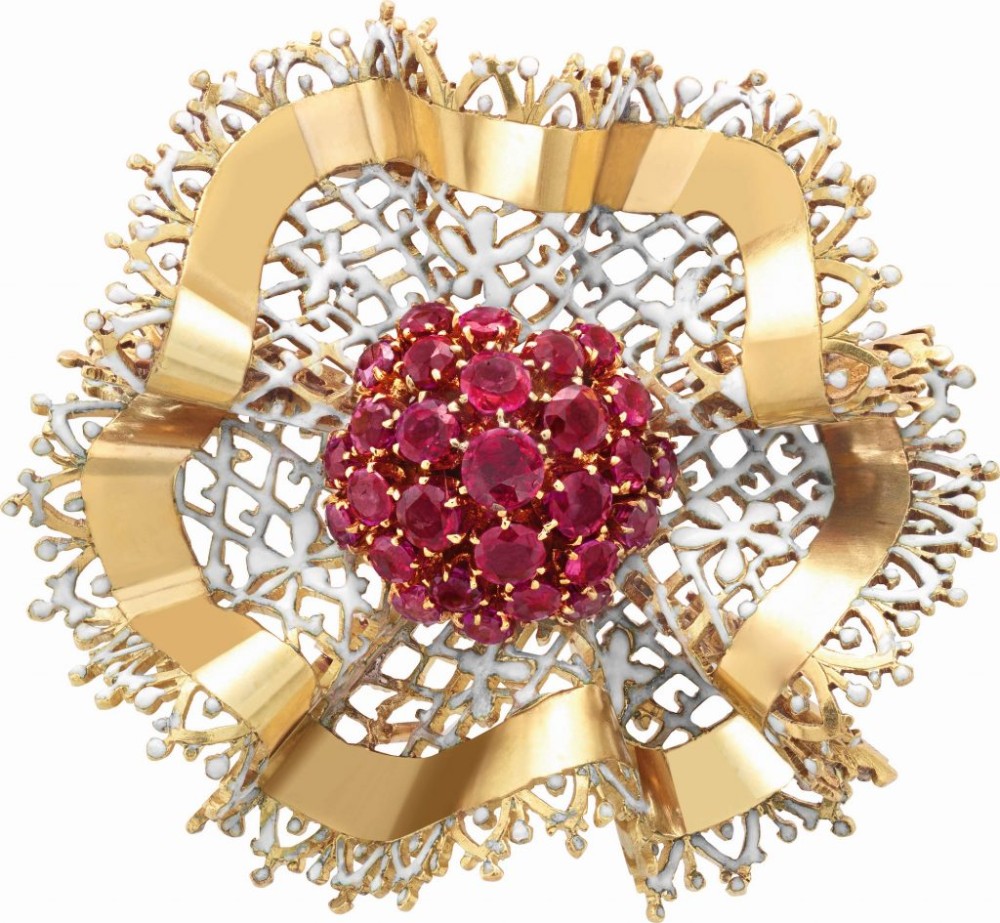

A ballet in three acts, each one revolving around a precious gemstone – emerald, ruby and diamond – Jewels was a ballet rumoured to have been inspired by the friendship between Balanchine and jewellery house Van Cleef & Arpels, where Balanchine and dancer Suzanne Farrell went to meet the press to publicise the new production in 1967.

The jewellers had been making ballet clips since the early 1940s, according to Nicolas Luchsinger, director of the Heritage collection and president of Van Cleef & Arpels Asia Pacific. “Since then, Van Cleef & Arpels has never stopped creating ballerina clips, which are still part of the Van Cleef & Arpels DNA, with their distinctive rose-cut diamond heads. Mr Balanchine even offered one of these ballerina clips to his wife,” he says. “The creation of the ballet Jewels is a milestone in the history of classical dance and was really the first time that such a creation was based on the friendship of a choreographer and a jeweller.”

The jewellery maison has kept up its patronage of ballet and supported many worldwide dance initiatives, working with famous choreographers of today such as Benjamin Millepied. The title sponsor of the Hong Kong Ballet’s production of Jewels this year, Van Cleef & Arpels have set up an exhibition of the ballet clips at their Central

flagship. “It’s a great opportunity to familiarise oneself with the influence of ballet in Van Cleef & Arpels jewellery. For the first time these rare pieces from the Patrimony collection, which have never travelled so far, have finally come to Hong Kong,” Luchsinger says.

“One of my favourite pieces in the selection is a ballerina clip in which the body, face and clothes are completely paved with rosecut diamonds. It’s one of the first clips designed by Maurice Duvalet in New York. These rose-cut diamonds are supposed to have come from the Spanish royal family in the 19th century and were sold after the Spanish Civil War.”

Jewels has gone down in dance history as one of Balanchine’s more emblematic works, embodying the choreographer’s style of narrative-free ballets set against minimal sets and costumes. It is, as White explains, an exploration of the characters and dance styles he was intrigued by within his own company.

“With the first act Emeralds, the main dancer, the one that dances the most, was inspired by an incredible French ballerina named Violette Verdy who was trained at the Paris Opera. She had this incredible effervescent personality, and she loved to eat and she loved to talk. She was really, as the French would call it, a bonne vivant. She knew how to live, which is a very French quality and took pleasure in things that delight the senses – perfume, jewels and everything,” White says.

“We didn’t work on that solo today but when you see the ballet, you’ll see the solo that she does and it starts out with these hand gestures – sort of like a French woman at her toilette, spraying herself with perfume and admiring her jewels before she goes out. She was very delicate, feminine and had a very fragile quality to her and that’s Emeralds.”

Rubies takes a more masculine turn. The second act of the ballet, characterised by jazz and a piano accompaniment, sees steps done without turn out, that famous outer rotation that characterises classical ballet. “Rubies was created and there were three principal roles and the ballerina is Patricia McBride. She came from New Jersey, which probably doesn’t mean anything to you, except that, let’s just say she was very unsophisticated but not in a crass way. She was just unpretentious and had lots of energy – just really nice movement with a natural quality, and she could do anything with an incredible amount of energy.

“Edward Villella, her partner, had grown up on the streets of the Bronx in New York in an Italian community, which was really tough, and from his early childhood he had to fight. He was a street kid and a professional boxer at some point. He started ballet because he had to go with his sister when she was taking ballet classes. He had so much energy the teacher snatched him and said he had to take the class. Of course he hated it, but then he started to like it, especially when he realised he was surrounded by girls,” White continues.

“In Rubies, the male dancer does a lot of running, like running on the street and there’s even images of boxing. It was very much his character, sort of an animal tough guy and brilliant virtuoso. There’s also a central ballerina role, which was created for a very tall woman. She was like 5’10 and so strong. She could do any of the men’s steps and all of her steps are really bold. There are some really high extensions so you see a lot of these big, long legs. I know 1967 sounds really, really old but it was the time of the Beatles and hippies and things like that. It wasn’t that conservative but a lot of Balanchine’s choreography looked radical even at that time.”

The final act, Diamonds, is more in the classical Russian tradition. With no solos, just pas de deux and a large cast, Balanchine still managed to put his own stamp on it. “He loved royalty. He grew up in St Petersburg, a magnificent imperial city, and ballet comes from the royal courts in Europe, so port de bras are from courtly gestures,” says White. “It’s more traditional choreography but traditional with a twist. Everyone in the corps de ballet has to dance like they’re the only person on stage. That’s also the case of how we worked when we were in the New York City Ballet. Balanchine liked to see that you still had your own personality when you were on stage.”

In a way, there could not be a ballet more suited than Jewels to inspire Van Cleef & Arpels’ ballet collection. “In a ballerina clip, designers try to capture the exact gracious movement of the dancers. As choreography evolved over the past 80 years, it’s interesting to compare the different movements of the ballerinas through time,” Luchsinger says. “In the Jewels production, the diamond represents the Russian ballet repertoire, the emerald French and the ruby America, and we built a 2007 collection around these three precious stones.”

Perhaps, though, the most precious jewel is the legacy of a body of work as great as Balanchine’s that only a répétiteur can pass on. “For dancers, we can only pass it down from teacher to student directly. You can’t learn it from a book. You can’t learn it online. It’s the only way. Once you do it, it’s not like you can make a painting and it’s there forever,” White explains. “It’s a very precious and fragile art form – the most fragile – but in the work that we can see, like Jewels, it’s so beautiful and the work will last forever.”