The struggle for mental health in Hong Kong

Jan 02, 2018

Globally, it’s estimated that one in four people experience a mental health problem. Half of them say that the associated isolation and shame is worse than the condition itself. But what is mental health exactly, and at what point does it become a problem? The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of mental health runs thus: “A person’s condition with regards to their psychological and emotional well-being.” One of the reasons its state can be hard to pin down is precisely because it’s not a black- or-white issue. Mental health, just like physical health, has different patterns of health and illness. And those who may be sufferers, or early sufferers, are often the last to know. In the worst – and often most prevalent – scenario, they may feel the stigma of their condition prevents them discussing or sharing it with others.

“There are severe and potentially lifelong conditions that can be managed effectively, but may not always be ‘cured’ or prevented,” says the co-founder of the Patient Care Foundation, Dr Lucy Lord, who oversaw the inaugural Hong Kong Mental Health Conference last November in the city. “In the physical illness realm, this includes multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease, ulcerative colitis or cardiomyopathy. In mental health, this includes the diagnoses of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and other psychoses.”

There are also the more common disorders, which in mental health can take the form of anxiety, depression, panic attacks and addiction; such diagnoses have more in common with obesity, diabetes and coronary artery disease. In terms of the roots of physical and mental health, it is well-understood that we inherit a genetic predisposition, on which our early environment can have a significant effect. However, what we sometimes forget is that it is the way we live our life that massively impacts whether we will suffer from problems later on.

Mental health and its repercussions are often cited as the malady of contemporary living and 100 years of mankind’s accelerated commercialisation. “Urban environments have changed the type of threats to our well-being and our response to threat has also changed, with many of our behaviours being maladaptive,” says Lord. “We no longer have to run to catch our food, and highly processed carbohydrates and fat-heavy food is available in plenty – hence the massive increase in obesity, diabetes and heart disease. We no longer face threats in mutually supportive groups – families or tribes – but deal with chronic stress as isolated individuals, often living away from our families and established friendship groups.

Related: One Ten is out to save Hong Kong’s youth with workouts

Over time, this mismatch of our psychological make-up and our external environment can give rise to anxiety and depression. The tendency towards self-medication with drugs and alcohol can then lead to addiction. Rates of those physical conditions such as obesity, diabetes, along with common mental health problems, are very similar across populations, leading to the idea that these conditions are linked by our environment.

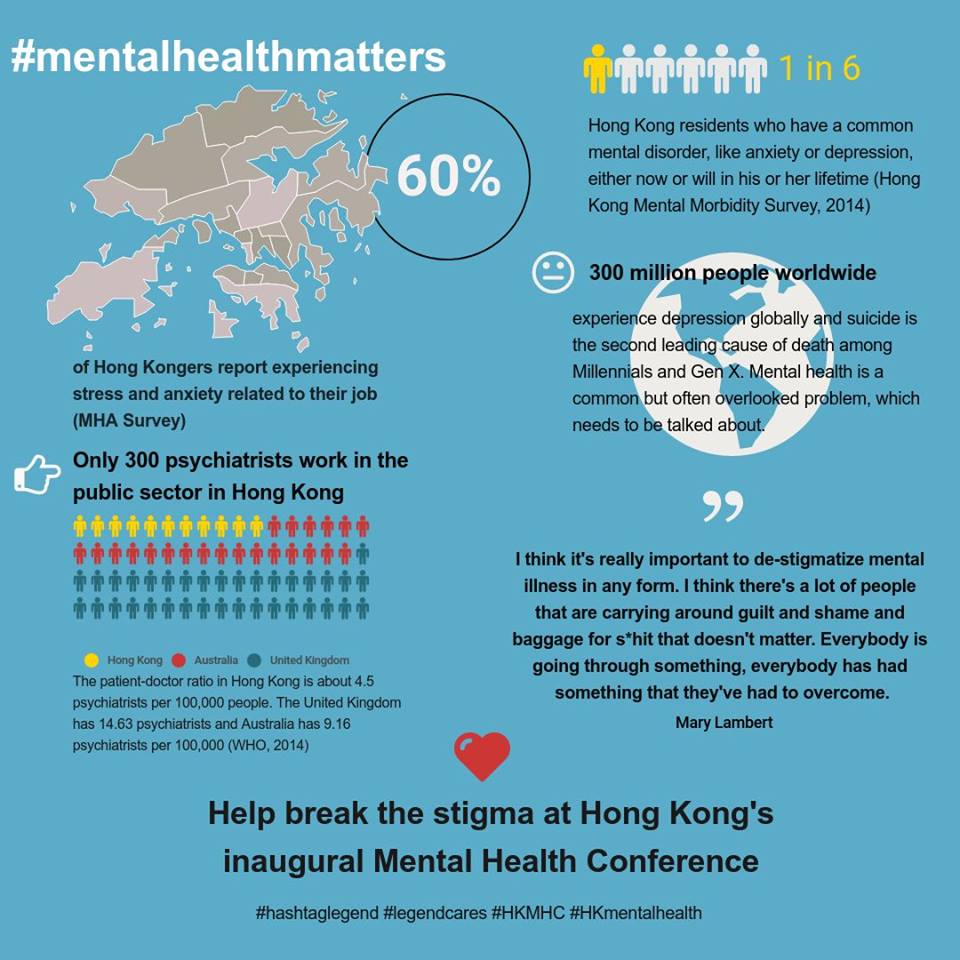

Recent studies have suggested that at any one time, one-in-six Hong Kong residents have a diagnosable mental health problem and everyone in the city has a one-in-four lifetime risk for a diagnosable mental health problem. This is a huge number – yet the problem is too often overlooked, relative to physical health.

“What is so frustrating is that these common mental health problems can be prevented and managed, so that most people make a complete recovery,” says Lord. However, typically, a delay in recognition, early intervention and treatment – compounded by the absence of a supportive, inclusive and non-judgemental culture – means that those one-in-four Hong Kong residents may not get the help they need and deserve.

One-third of the global burden of mental illness falls on China and India, where millions go untreated because of stigma and lack of resources. In China, less than 6 per cent of people with anxiety and depression, substance-use disorders, dementia and epilepsy seek treatment, while in India, only about one in 10 people is thought to receive specialist help. A fundamental reason behind this is stigma – an issue that needs to be addressed on a global scale, not only in Hong Kong.

Given the scale of the mental health problem and the public’s lack of awareness, or an inability to recognise the disorder in themselves or others, what are Lord’s immediate priorities? She cites the mission statement and vision that led to the founding of Mind HK, an initiative of the Patient Care Foundation that organised the November conference. First, it is to ensure that everyone in Hong Kong struggling with a mental health problem has the recognition, support and respect they need to make the best recovery possible; second, it’s to provide partnerships, collaboration, training, innovation and best practices to facilitate the work of all those involved in improving mental health in Hong Kong.

And finally, it’s “to lead, promote and support the destigmatisation and transformation of community mental health care so that Hong Kong can become a global leader in the eld and a model for other Asian cities,” says Lord. “We need to research and audit these strategies and share them internationally.”

Hong Kong also has a manpower problem when it comes to mental health; it has the lowest number of psychiatrists per capita in any economically equivalent global city. “We have some of the longest waiting lists for assessment of a new mental health problem in the world, with many patients waiting more than two years before being seen,” says Lord. “We do not think the current government is planning to revolutionise mental health funding; therefore, we need to find innovative, comprehensive and cost-effective interventions to help ourselves and our families.”

If manpower is the problem on the outside, then Psychiatrists, oversee stigma is the scarlet letter of the inside – the hampering factor in the development of better mental health care and in the prevention of suicide. It works at multiple levels and insidious ways. For many sufferers, there is the widespread perception that admitting to a mental health problem will lead to discrimination, isolation and prejudice in school or in the workplace, or that it may effect social status and reflect negatively on the family. At the most damaging end of this scale, women in Hong Kong who give birth to stillborn babies or miscarry during pregnancy are often held personally responsible for the loss, as though their neglectful or irresponsible lifestyle is the reason behind the tragedy.“It all means that symptoms of poor mental health are likely to be suppressed, ignored, or deliberately misattributed or misdiagnosed,” says Lord. “This results in fewer opportunities for prevention or early intervention. Problems may be recognised only when it is too late or incredibly difficult to change outcomes.”

Eighteen months before actor Leslie Chung took his own life by jumping from the top floor of Hong Kong’s Mandarin Oriental hotel on April 1, 2003, he contacted Time magazine, a publication he knew well, and suggested a cover story in which he reveal his life as a homosexual celebrity who’d had to lead a double-life. While to Chung and his fan base, it was clear where his sexual preferences lay, it wasn’t a subject he, or they, could comfortably discuss in public.

Chung spoke to this writer several times, always in the Mandarin Oriental, casually delivering the line: “It’s not like I’m about to jump out of the Mandarin Oriental and kill myself.” Eighteen months later, that’s exactly what he did. Time never ran the proposed and extensively prepared cover story. After numerous interviews and anecdotes about his life, his loves and preferences, Chung called the magazine and cancelled the story. Like the late, great showman he was, he left it until the morning of the final day (Time was printed on Saturday evenings in Asia) to inform us. The message, as clear as a bell today, is still chilling. In saving his reputation, he was denying – and ultimately killing – himself.

Chung’s times were different times, especially in terms of technology. With the prevalence of social media platforms like Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram – on the last of those, we’re posting more than 34.5 billion posts per annum, and wondering what the short- and long-term damage might be – when do we stop using them and they start using us, or has that subliminal shift happened already? Sean Parker, the former president of Facebook, recently made the following observation about social media: “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains. The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops we’ve created are destroying how society works.”

And simultaneously increasing the incidence of addiction – we have become absolutely addicted to social media. As a writer and editor who continues to use a Nokia flip phone over a smartphone, I increasingly incur the envy of those bees of the invisible who have leapt onto the Scylla and Charybdis of smartphones and social media, and whose lives and value have seemingly become the superficial barometers of the numbers of likes, shares, retweets and so on. Yet all of it is a digital affirmation of unknowable provenance – a series of seemingly distorted opinion polls reflecting the popularity of an individual.

And here’s why the digital addiction is so dangerous as opposed to the real world. On social media platforms, unlike face-to-face interactions, you can literally buy happiness from anywhere and anyone and anything you like. It’s a hot debate right now in publishing that the global industry may be living under this entirely false pretence, in which none of the numbers add up – and even when they do, it doesn’t make sense. It’s extreme paranoia and mass delusion, an industry-wide mental health disorder.

How does Lord assess the digital threat in this context: as a mental health disorder? “Social media, one of the many changes in the way we live today, has had an adverse effect on our mental health,” she says. “Fake news, fake lives, fake competition, fake looks and, most importantly, fake empathy and rapidly changing loyalties have a very poor impact on friendships, self-esteem, group support and trust.” Hence the words of Parker.

Yet Lord, positive and upbeat to the last, upsells the benefits that digital at its most definitive could be a positive. “While social media is one of the causes of our decline in good mental health and well-being, it may yet become its salvation. Online tools and individual digital interventions are economically viable and scalable solutions, which may allow everyone access to prevention and early intervention for their mental health problems.”

Social media platforms could yet become efficacious e-speakeasies that offer a salvation to those with mental health disorders – but with one major and mass proviso: stop liking each other and start listening instead. That’s when the real learning starts.

In a world so accelerated and agitated by electronic excitation every second on multiple platforms, how do we know when we might become the subject of mental health illness, analysis and study? What are the signs?

“In Hong Kong, doctors and therapists notice that many mental health problems present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, headaches and back pain,” says Lord. “All of these are common manifestations of suppressed emotional pain. When these occur with other symptoms such as insomnia, loss of concentration, fatigue, irritability, tearfulness or withdrawal from usual social interactions, they may indicate a mental health problem.”

Information on how to diagnose and manage mental health problems in yourself and those that you care about, and how to improve well-being, can be found on the Mind HK website at mind.org.hk in English and Chinese.

If you are feeling stressed or are in need of support, you can also contact the Samaritan Befrienders’ 24-hour hotline on +852 2389 2222, Suicide Prevention Services on +852 2382 0000 or the Society for the Promotion of Hospice Care on +852 2868 1211.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2018 print issue of #legend