L’Ecole Asia Pacific takes us on a journey with minerals

Sep 19, 2024

L’Ecole Asia Pacific’s latest exhibition, Journey with Minerals, is an invitation to rediscover the world around us. Co-curator Dr Eloïse Gaillou takes Stephenie Gee through the multifaceted nature of minerals and their profound influence on our everyday existence

Minerals make the world go round, literally. They are the fundamental constituents of the Earth’s crust, serving as the building blocks upon which the planet’s landscapes are constructed. Geological significance aside, these natural compounds have been integral

to human progress, for good or evil.

They have dictated how we build, eat, communicate, wage war, create art, travel and worship. Some, like copper and iron, lend their names to the ages of mankind. Others, such as gold, silver and diamond, contributed to the rise and fall of great empires. Without them, we could not maintain any form of civilisation beyond the most primitive.

Take the house we live in: the walls are set with cement, made of limestone, clay and gypsum. The windows are glass, a product of silica sand. We wash in water that has come through copper pipes and runs through a brass tap, plated with nickel or maybe chromium. In the morning, when the modern woman goes to work, the powder she applies to her face is a derivative of talc, and her jewellery is made of gold or silver, sometimes studded with emeralds, rubies, sapphires or even diamonds. The present is truly an age of minerals – many minerals. But perhaps because they are so ubiquitous, it’s easy to forget how completely we depend on them.

Minerals make the world go round, literally. They are the fundamental constituents of the Earth’s crust, serving as the building blocks upon which the planet’s landscapes are constructed. Geological significance aside, these natural compounds have been integral

to human progress, for good or evil.

They have dictated how we build, eat, communicate, wage war, create art, travel and worship. Some, like copper and iron, lend their names to the ages of mankind. Others, such as gold, silver and diamond, contributed to the rise and fall of great empires. Without them, we could not maintain any form of civilisation beyond the most primitive.

Take the house we live in: the walls are set with cement, made of limestone, clay and gypsum. The windows are glass, a product of silica sand. We wash in water that has come through copper pipes and runs through a brass tap, plated with nickel or maybe chromium. In the morning, when the modern woman goes to work, the powder she applies to her face is a derivative of talc, and her jewellery is made of gold or silver, sometimes studded with emeralds, rubies, sapphires or even diamonds. The present is truly an age of minerals – many minerals. But perhaps because they are so ubiquitous, it’s easy to forget how completely we depend on them.

Enter Journey with Minerals, presented by L’Ecole Asia Pacific, School of Jewellery Arts, in collaboration with the venerable Mines Paris - PSL Mineralogy Museum. The exhibition, which runs until October 31, brings together some 40 mineral exhibits from the museum – whose mineralogy collection is one of the most comprehensive in the world – showcasing the profound forms, diverse applications and artistic value of these geological wonders through the lenses of Matter, Jewellery, Technology, Arts and Space.

“We’ve been working with L’Ecole since 2017 because we have a lot of things in common. For us, it’s not the mining part that is important but the industry part, the savoir faire, the transformation of a natural resource into an useful piece of object. L’Ecole has all these exhibitions and programmes about gemstones and jewellery. But before gemstones are gemstones, they’re minerals. So the purpose of this exhibition is to explain what minerals are and, besides as gemstones in jewellery, what they can be used for,” explains Dr Eloïse Gaillou, the exhibition’s co-curator, and curator and director of the Mineralogy Museum.

There were many loans that did not materialise – not owing to their value but rather the exhibition environment. “Here you have the problem of humidity. So we had to choose pieces that are not too sensitive to that because there are some water-rich minerals and if the humidity is constantly changing, water will be going in and out of the structure so it’s not stable. For example, opals interact a lot with water,” Gaillou explains. “Another thing is that we have direct sunlight and that’s not good. We had to be really mindful about these things – we had to select pieces that wouldn’t suffer from the environment.”

The showcase opens with Matter, which defines what a mineral is. “We feature minerals that display perfect shapes to show off the fact that they are natural crystals, which are organised matter. And they look man-made – the shapes and arrangements are so perfect you can’t believe nature did it,” she says.

Take the pyrite. “Only in Romania, in the Boldut mine, will you find pyrite perfectly spherical like this. It looks fake but it’s completely natural and that’s what I love about it. Pyrite is composed of two chemical elements – iron and sulphur – which at a microscopic scale you will see combine to form a cubic structure. And it’s because it has that arrangement at the atomic scale that pyrite can form different shapes. Like Lego, by stacking these cubes you can make a sphere, a cube of course, and also many other shapes. Minerals can be classified into seven crystal systems, and here we show three. Pyrite represents the cubic system, calcite the trigonal, and fluorapatite the hexagonal.”

The most extensive section of the exhibition, Jewellery traces the path of gems from their origins in the igneous depths to their sparkling forms in cherished adornments. Finished pieces like a Georges Fouquet 80-carat octagonal-cut aquamarine pendant and a graduated ruby and diamond necklace circa 1980s rub shoulders with raw uncut tourmalines, a 6,520-carat aquamarine – the most valuable specimen in the space – and a thin, 90cm-tall slice of nephrite jade gifted to the museum in 1867 by French merchant and explorer Jean-Pierre Alibert. “There were many challenges putting this exhibition together, but for me the most difficult thing was bringing the jade,” Gaillou tells me. “It’s pretty, it’s valuable and it’s historic. I’m very happy it arrived intact with all the transportation that it took to get it here. But what makes me even happier is that in our museum you cannot see through the jade because it’s placed next to a wall, but here we were able to put some back lights so you can really experience its colour, transparency and diverse patterns.”

Some 6,062 official mineral species are recognised today, with an infinite variety of properties, shapes, colours and textures.The next section Technology explores those that have shaped our scientific endeavours like copper, which is everywhere and in everything (an electric vehicle, I’m told, contains more than 80 kg of copper, three times more that its combustion counterpart). Art, meanwhile, presents those prized as rare pieces of natural art. During the 17th century, French king Louis XIV collected sandstone concretions known as gogottes, featuring a sculptural silhouette reminiscent of the human body. Gongshi, or scholar’s rocks, have been cherished since ancient times by China’s intellectual elite as objects of contemplation. Eroded into intriguing shapes, these beguiling mineral formations often resemble landscape scenery like mountain ranges.

“Humans get inspired by nature, and nature is natural art as well. So the Art section is very

subjective – everyone will look at a piece and think and feel something different,” Gaillou says. A lustrous cluster of prismatic stibnite blades, for example, echoes the skyscrapers in the view beyond. And beside it, a slab of rhyolite embedded with opals bears a striking resemblance to a human face. “This is a piece that we’re going to miss a lot at the museum because I walk past it every morning and it says hi to me. My colleagues were so bummed too when I told them we were bringing it over.”

Some 6,062 official mineral species are recognised today, with an infinite variety of properties, shapes, colours and textures.The next section Technology explores those that have shaped our scientific endeavours like copper, which is everywhere and in everything (an electric vehicle, I’m told, contains more than 80 kg of copper, three times more that its combustion counterpart). Art, meanwhile, presents those prized as rare pieces of natural art. During the 17th century, French king Louis XIV collected sandstone concretions known as gogottes, featuring a sculptural silhouette reminiscent of the human body. Gongshi, or scholar’s rocks, have been cherished since ancient times by China’s intellectual elite as objects of contemplation. Eroded into intriguing shapes, these beguiling mineral formations often resemble landscape scenery like mountain ranges.

“Humans get inspired by nature, and nature is natural art as well. So the Art section is very

subjective – everyone will look at a piece and think and feel something different,” Gaillou says. A lustrous cluster of prismatic stibnite blades, for example, echoes the skyscrapers in the view beyond. And beside it, a slab of rhyolite embedded with opals bears a striking resemblance to a human face. “This is a piece that we’re going to miss a lot at the museum because I walk past it every morning and it says hi to me. My colleagues were so bummed too when I told them we were bringing it over.”

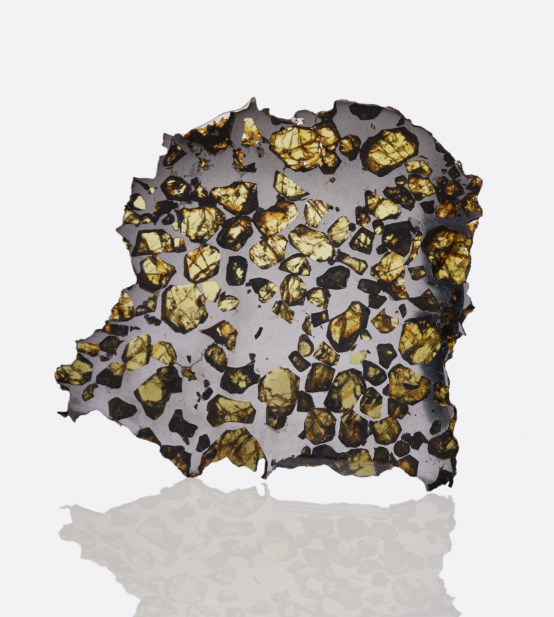

The exhibition draws to an end with Space. Among the exhibits here are pallasite, a class of stony- iron meteorite; and moldavite, a rare green tektite formed 15 million years ago by meteoric impact. “Minerals are the building blocks of Earth, but they’re also the building blocks of former planets and former fragments and everything that is solid floating in the solar system,” Gaillou says. “Minerals are everywhere in our everyday life, we just don’t realise it.”