China as a Dystopian Artistic Vision

Apr 27, 2016

Klaus Biesenbach, internationally visible director of Moma PS1 in New York and chief curator at large at The Museum of Modern Art, has spent the last three years mounting star exhibitions with the likes of Björk, Yoko Ono and Marina Abramović. His Instagram feed, @klausbiesenbach, boasts 194,000 followers and scrolls an inventory of art and celebrity, on which it’s not unusual to see him post photographs with Lady Gaga in an elevator or organising Polaroids with Lana Del Rey and James Franco, or even Hong Kong’s art and lifestyle tycoon Adrian Cheng. Most recently he posted Donald Trump’s face as a pair of buttocks on legs and the tagline “read my lips” that has drawn almost 6,000 likes.

An exhibition at PS1, thus becomes more like a show, an occasion, and so it was with leading Chinese artist, Guangzhou-born, Beijing-based Cao Fei and her first solo show in the United States. Like the good sport she is, Cao entered into the spirit all guns blazing, hip-hopping with rap band the Notorious MSG, who performed at the show’s opening, mutually Instagramming her adventures in New York, taking the subway with Biesenbach, and even posting shots of Cheng. Cao, often described as one of the mainland’s most innovative young artists – she’s 37 with two children – and its leading female artist, has 4,500 Instagram followers, including the illustrious Emmanuelle Béart, French actress and now professional photographer.

In keeping with these times of instant likeability, one week after the show opened (until August 31), Cao was conveying her gratitude to Biesenbach electronically. “I love this show not because it’s my first US museum show, but it is much more that…a joyful process and rich experience.”

And there’s much to like about the PS1 show. Cao creates dystopic multimedia projects that explore the experiences of young Chinese citizens as they develop strategies for overcoming and transcending the realities of a rapidly changing society. Mixing social commentary, pop aesthetics, references to Surrealism, and documentary conventions in her films and installations, she reflects on the swift and chaotic changes occurring in Chinese society, in a thematic mash-up of social realist with escapist make-believe.

This interplay between fantasy and reality animates much of her work. In Cosplayers (2004), comprised of video and photography, the artist embedded herself in Chinese cosplay communities, dressed as imaginary Japanese anime characters. In wild and complex outfits, cosplayers romp around Guangzhou – a city known less for its imaginative character than for its industrial manufacturing – in hyper-reality and no little pastiche. It’s like fantasy vérité.

Cosplayers showed in New York, at Lombard-Freid Fine Arts, in 2005. Jane Lombard, co-founder of the gallery recalls premiering the experience. “We had seen images from Rabid Dogs and a video, shown at the International Centre for Photography in New York, which was always a strong promoter of her work. Christopher Phillips, the ICP curator, is a big fan.” But reputations in the art world aren’t always made overnight. “It does take time to create a market for a new artist, and as Chinese contemporary began to be popular, interest in Cao Fei’s work increased.”

Phillips was one of the first to bring Cao’s work to the US and still stays in regular contact with the artist. He heard of her growing reputation through Meg Maggio, then director of the Courtyard Gallery in Beijing. The video Rabid Dogs was included in a major ICP exhibition called Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China. “Rabid Dogs was the first work that visitors saw when they entered ICP, and it got a lot of attention,” says Philips. “They were fascinated by the video, in which actors portraying dogs dressed in Burberry-inspired outfits battle with one another in a modern office setting. Rabid Dogs mixes a satirical look at nascent Chinese consumer culture with a bold portrayal of what Cao calls “the class struggle in the modern workplace.”

Lea Freid, co-founder of the gallery, said both works distinguished Cao from other Chinese artists who were engaged in more didactically aggressive performance works that were critical of the Chinese government. “Her work was a subtler comment on the rapidly changing aspects of Chinese society. She was clearly a product of a younger generation growing up in Guangzhou which was geographically positioned as part of the New China in terms of where all the new experiments with the market were happening – Cao Fei was also more influenced by Western pop culture in terms of also being regionally closer to Hong Kong.”

Phillips considers Cosplayers one of Cao’s strongest works, still.

“It’s a kind of docu-drama about a group of high-school kids in Guangzhou who had adopted the Japanese cosplay culture and were acting out their own elaborate costumed dramas around the city. Who knew in 2005 that there were alienated teenagers in China living in their own self-created fantasy worlds? Probably no one other than Cao Fei.”

Even though by that time Chinese art was trending in New York, none had seen work quite like Cao Fei which was “so imaginative and so real at the same time,” says Freid. So popular indeed, that even the mailman and Fedex delivery guys took the time to view the work Freid recalls. “The popular appeal of Cao Fei’s work has always been strong and what sets her apart from many artists who don’t quite break the popular culture barrier. I’m happy to report not only did our staff receive inquiries almost daily from Phd students and curators but certainly look back fondly to know that our presentations of Cao Fei’s work in New York – Hip Hop, RMB City, Playtime, Haze & Fog and La Town were also appreciated by the food delivery guys.”

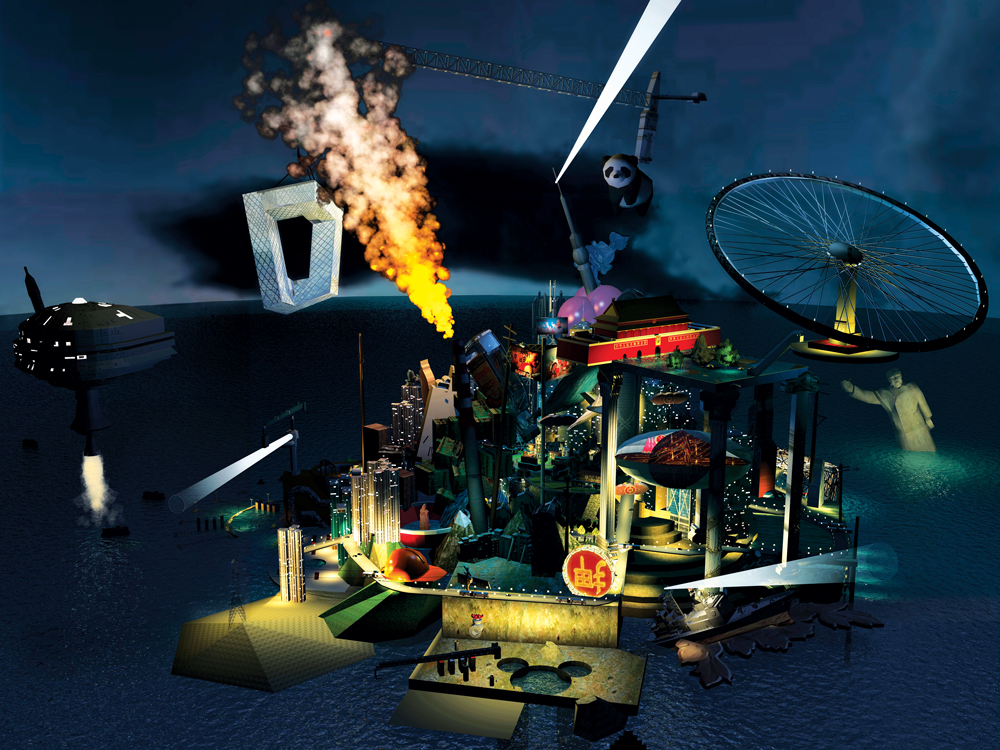

RMB City (2007) was as groundbreaking as Cosplayers, perhaps more so.

Using the Internet platform Second Life, Cao created an avatar named China Tracy, through whom she embarked on a search for a romantic partner, and spent several years developing a virtual city named after China’s currency. Cao combined what she calls “overabundant symbols of Chinese reality with cursory imaginings of the country’s future”. The result is a Technicolor playground of floating architectural icons – Tiananmen Square overrun by the Three Gorges Dam, a listless CCTV tower dangling from a crane – and aerial shopping malls bedecked with Mao statues.

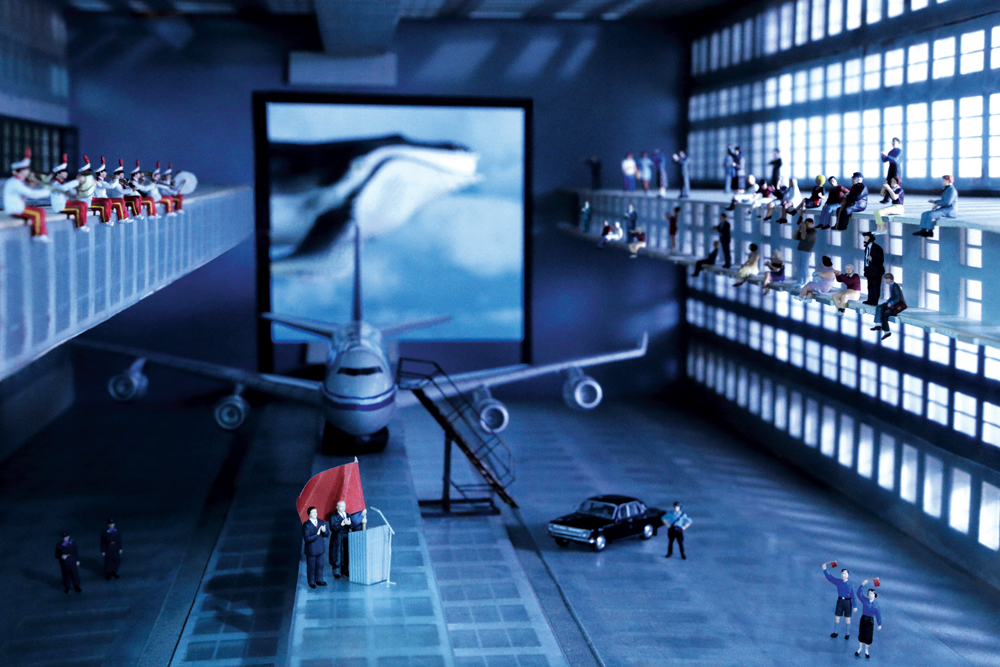

Lombard recalls showing RMB City in her gallery. “RMB City was instantly a hit and the installation in our gallery was sensational.” Phillips took a fully immersive approach to RMB City. “I was in touch with Cao Fei as she planned that project and launched it in the online virtual world Second Life in 2008. RMB City was far ahead of its time.” It allowed visitors to design their own interactive online avatars and create their own storylines based on encounters with other Second Life users in RMB City. “In 2009, I contacted Cao Fei by having my avatar track down her Second Life avatar. At that point I think that Cao Fei was spending most of her time online in RMB City. I invited her to create a new online work in RMB City that could be part of the Third ICP Triennial exhibition. She agreed and devised a special female avatar, ICP Seda, and a virtual billboard inside RMB City.” Visitors to the ICP exhibition space in New York could sit at a computer and manoeuvre ICP Seda around RMB City, as well as changing her look and outfits. “It proved to be an extraordinarily popular work, especially with younger visitors, and got quite a lot of attention in New York.”

Lombard recalls a sense of excitement working with Cao. “I accompanied her filming of Hip Hop in Chinatown and lower Manhattan. When she saw one of the Statues of Liberty wandering around in a park she decided she had to have him in the film. Persuading him wasn’t difficult and he was beyond cooperative. He then came (without costume) to the opening. The Notorious MSG performed and the crowd was in disbelief. It was a rousing opening.”

Interestingly, Cao’s father, Cao Chong’en is an accomplished sculptor and, as an artist of the state, spent much of his lifetime during the Cultural Revolution making statues of leaders, from Chairman Mao to Deng Xiaoping. Under her father’s influence she read about Western art and culture at a young age, worked as a set designer on television commercials after graduating from Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Her career as an artist was triggered by a call from Ai Weiwei, asking her to participate in the iconic group show with the Western expletive.

Pop culture, especially television, appears to have inspired the majority of Cao’s work. But she also identifies Japanese experimental artist-filmmaker Terayama Shuji as her greatest influence – a glance through his Buraikan, Hunchback of Aomori, and Emperor Tomato Ketchup shows why. His work was a trailblazing shift through varied media and performance and the Japanese refer to his output as being the “eternal avant-garde”. Like Terayama, Cao’s work exits in a liminal space between fact and imagination.

Witness Whose Utopia? (2006), a work commissioned by the Siemens Art Project, in which young workers at a lightbulb manufacturing plant Osram, in the Pearl River Delta region, role-play their own personal fantasies, dreams and aspirations – dressing up, pirouetting ballerina, performing tai chi or playing guitar – within their mundane industrial environment. Cao spent six months researching the project and talking with the workers.

Since then there’s been 2013’s Haze and Fog, currently showing at Tel Aviv’s Centre for Contemporary Art until mid-month, “a new type of zombie movie set in modern China” in which people live in the era of “magical metropolises” – Cao’s film is about the invisible miracles of these potentially lost stationary lives. This “magic reality” is created through a struggle at the tipping point between the visible and invisible.

Same Old, Brand New at Art Basel in Hong Kong 2015 was trademark Cao Wow fare; a “big art” project in which symbols, logos and moving images from video games such as Pac-Man and Tetris played out on the façade of the city’s 490-metre high International Commerce Centre in West Kowloon.

And this year’s La Town, a tour of an alternate reality modelled on our own, constructed from handmade models. The 40-minute film, a neo-noir about a mythical, post-apocalyptic city forgotten by time, but nonetheless animated by the political scandals, torrid love affairs, and environmental disasters that typify contemporary life, references cinematic classics such as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather and Hiroshima Mon Amour, blurring boundaries between reality and fiction. There’s even an old cinema (or theater as this is America) showing Gone With The Wind.

“I try to find different ways to connect and interact with society,” says Cao of her work. “At the same time, I am trying to construct a new model of society.” In all her work, by collapsing extreme versions of the everyday and the fantastical into one, the artist is able to vividly underscore the interior and exterior worlds of global, digital citizens navigating extreme change.

Phillips thinks her work is dynamic. “Cao Fei remains one of the best contemporary artists working anywhere. She’s a visionary whose works are all attuned to the future in a remarkable way. The word ‘impossible’ does not exist for Cao Fei. Her attitude is, ‘If I can imagine it, I can find a way to do it.’ I can’t wait to see what kinds of artworks she will be making in the coming decades.”

“Cao Fei is a keen observer of her rapidly changing country and manages to say just what she wants in various disguises,” says Lombard. For Biesenbach, she’s a global eye-opener: “It’s important for US audiences to see that people in Beijing can be just as hip as those in the US.” And seemingly like Cao, have a blast doing it.