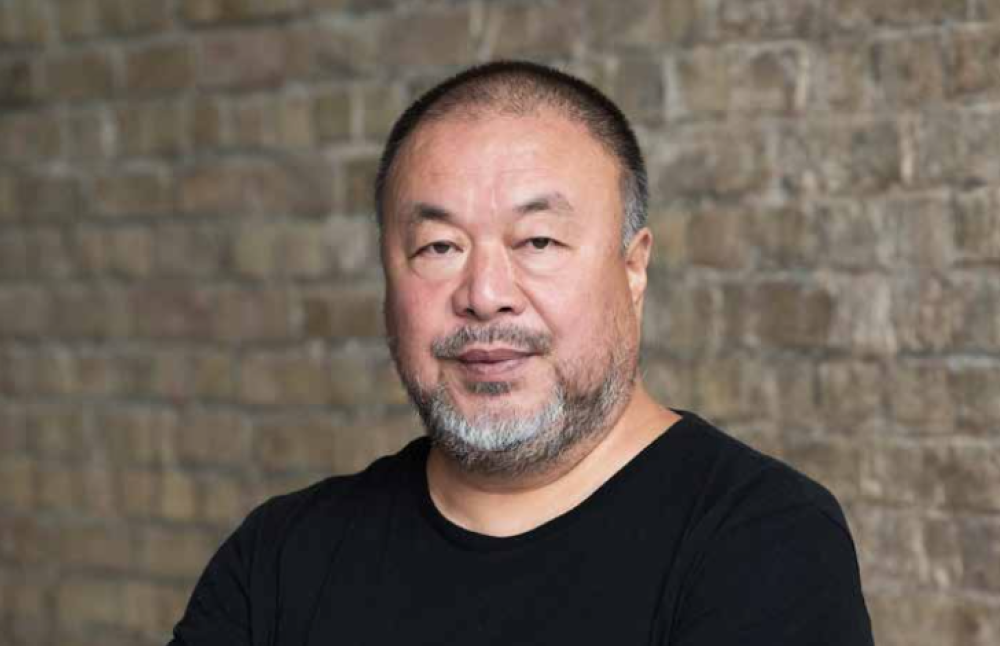

Ai Weiwei on his new show at Galleria Continua and freedom of expression

Aug 05, 2024

Ai Weiwei, who believes that creativity is the power to act and change the status quo, speaks to Dionne Bel about his new show at Italy’s Galleria Continua and being a fervent advocate of freedom of expression

Ai Weiwei, China’s most famous dissident artist and ardent defender of free speech, is outspoken and provocative. Over the years, he has been a critic of everything from the predicament of Rohingya refugees fleeing Myanmar to the US-Mexico border wall and authoritarian German society, openly and unreservedly airing his views through his art and on social media. In exile in the West since 2015, after having his movements and communications in China restricted, and being brutally beaten, imprisoned and fined by the Chinese state, he now resides in the Portuguese countryside, an hour southeast of Lisbon, where he is building a gargantuan studio. He had placed an offer on the 40-acre property after seeing it just once on his first visit to the country. It was all unplanned, much like most of his oeuvre, which he orchestrates based on intuition and circumstance.

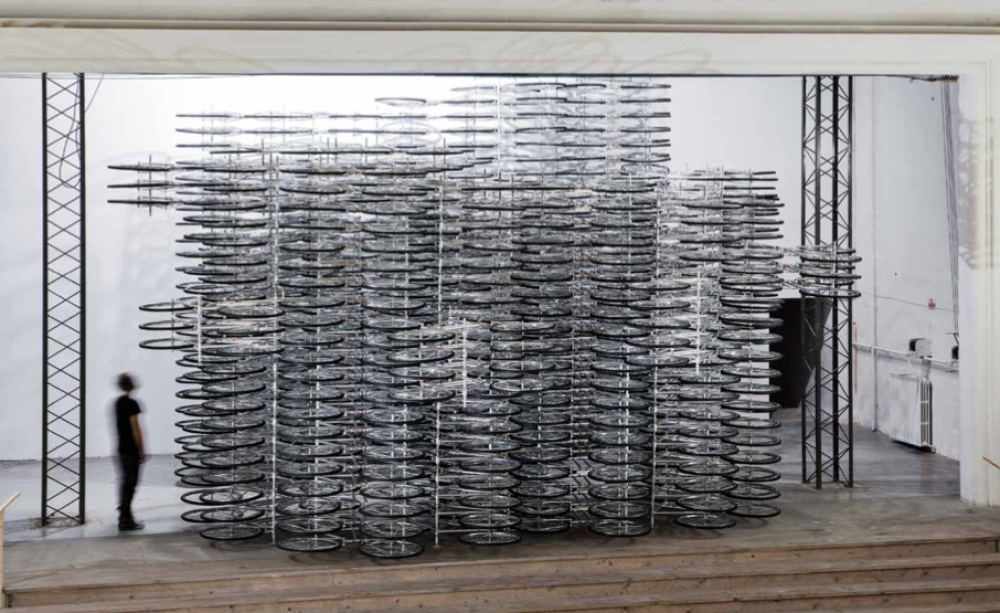

Self-taught (Ai dropped out of the Beijing Film Academy after two years and Parsons School of Design in New York after one semester), he works in multiple disciplines and in between them, refusing to define his work as sculpture, installation, architecture, design, photography or film. For his Fairytale conceptual project, he transported 1,001 Ming and Qing dynasty chairs from China to Kassel, Germany, along with 1,001 ordinary Chinese citizens to explore the city as part of the Documenta 12 contemporary art exhibition. Then he filled the Turbine Hall at London’s Tate Modern with 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds meticulously hand-crafted and painted by 1,600 Chinese artisans as a metaphor for both the downtrodden, conformist Chinese populace and the power of the masses.

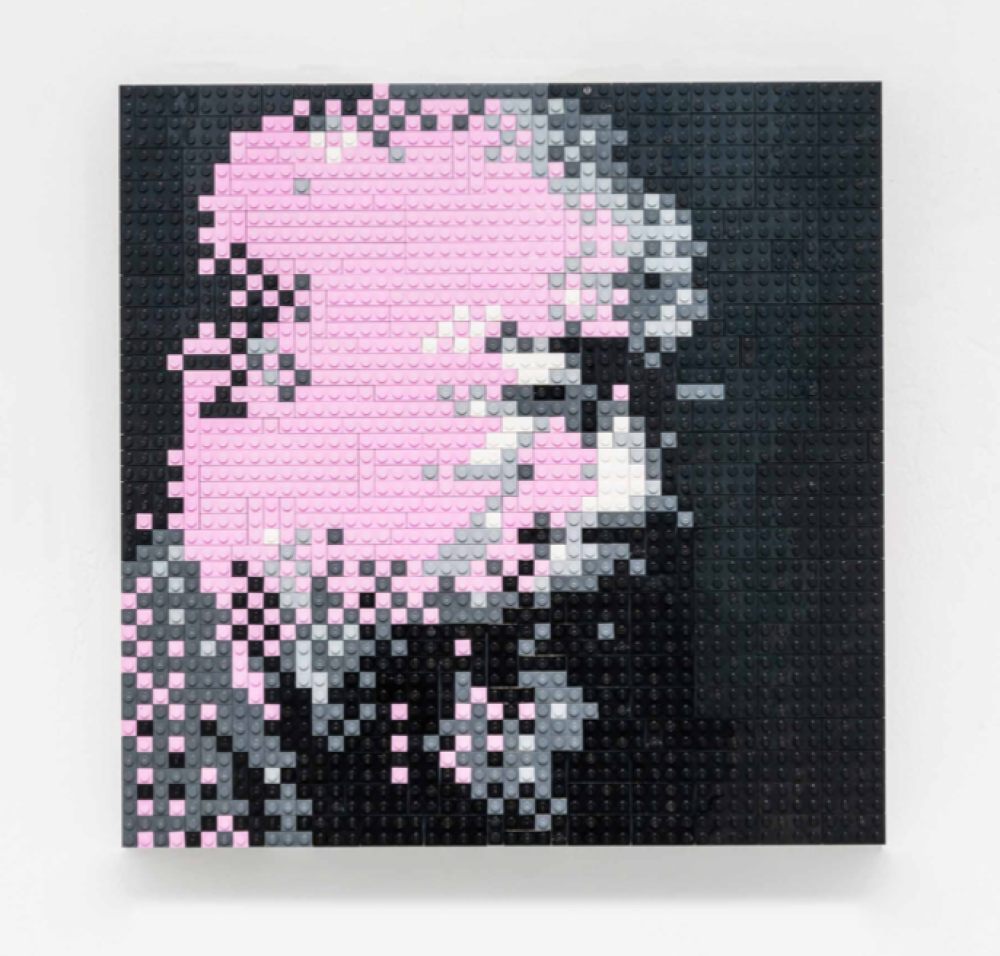

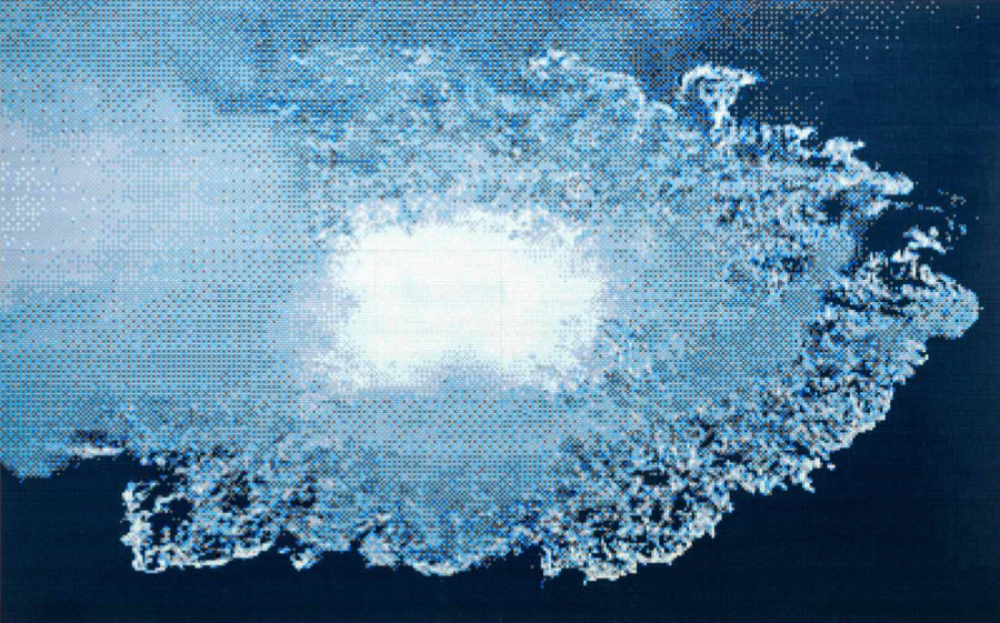

Calling attention to the planet’s humanitarian catastrophes, Ai tackled the global refugee crisis with

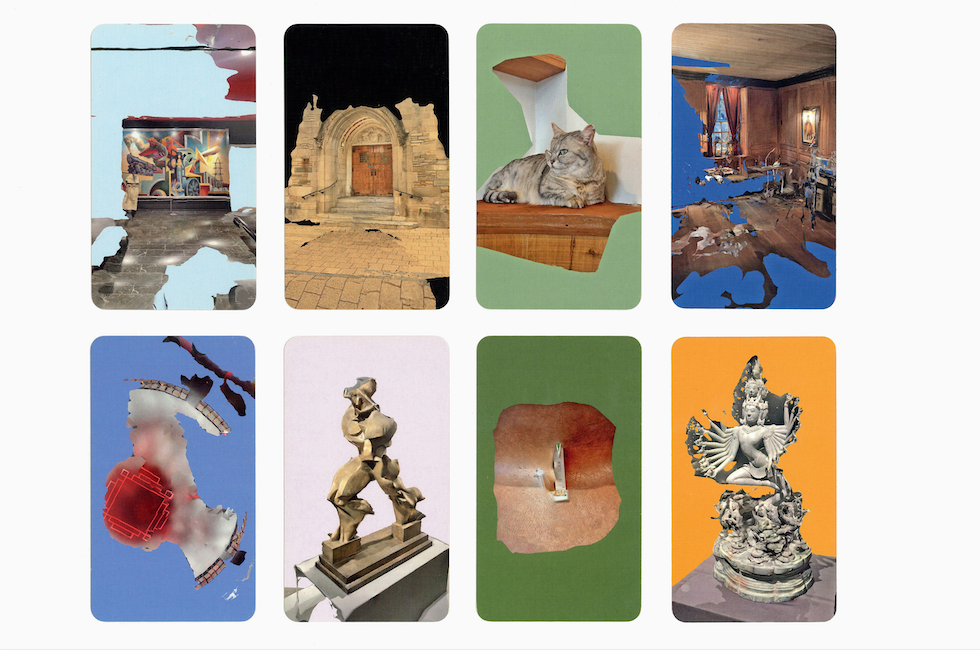

an installation of 14,000 life vests attached to the columns of the Konzerthaus Berlin concert hall that he had collected on the Greek island of Lesbos, and made the documentary Human Flow following the plights of millions of displaced persons across 23 countries through intimate interviews of individual refugees and drone footage of vast migrant camps. Taking on Western art history, he reinterpreted Claude Monet’s Water Lilies using 650,000 Lego pieces, and his fixation with the toy bricks is now abundantly on display in his solo exhibition Neither Nor, on view through September 15, 2024 at Galleria Continua in San Gimignano in Tuscany.

Also see: Pastry chef Janice Wong on creating art with desserts

You work across various mediums, including sculpture, architecture, installation, performance, photography, film and even artificial intelligence. How do you decide which medium to use for a particular project?

I really don’t know. During the pandemic, everybody was shut off. So I thought maybe I’ll make a print on some masks, which sold on eBay and very successfully gathered US$1.5 million to give to Refugees International, Doctors Without Borders and Human Rights Watch. It’s always intuitive because I don’t have a real purpose to call myself an artist. I would immediately have an idea, a bad idea. Since young, I’ve been full of bad ideas, and I have the ability to bring them to life. That takes a long preparation to investigate, organise people or write reports. A lot of people share my ideas, but it’s not planned – it’s by intuition. Maybe this afternoon I’ll think something is funny, then we will start making it. We don’t calculate the cost or analyse, so that gives us some kind of liberty.

Many of your works are monumental in size. What do you like about scale and accumulation?

I think it’s because I grew up in a Communist society. We used to work in the fields, and each person took care of one line. We cared for hundreds, just walking all the way until we could not even see the people anymore. It left an impression on me because size can create a new dimension. For me, a

single artist in his studio, stretching a canvas and using one brush was never sexy, but even two persons working together is already interesting because it relates to communication and organisation. If it’s 1,000 people painting sunflower seeds, I think it’s beautiful.

People brought those seeds home, and after eating and putting their children to bed, they started to paint a few, or between lunch and dinner, if they had two hours, they painted some for extra cash, and they all enjoyed it so much. So I think that’s very attractive; it’s more attractive than showing works in museums. My team in China is making another work now using buttons I bought on Twitter because a button factory was closing down and the buttons were going to a landfill, so suddenly I had 30 tonnes of buttons. I became the king of buttons. Then it took us years to figure out what we had: 9,000 types of buttons with different names, sizes and designs. Now, finally, I’ve found a way to put them together to make an artwork.

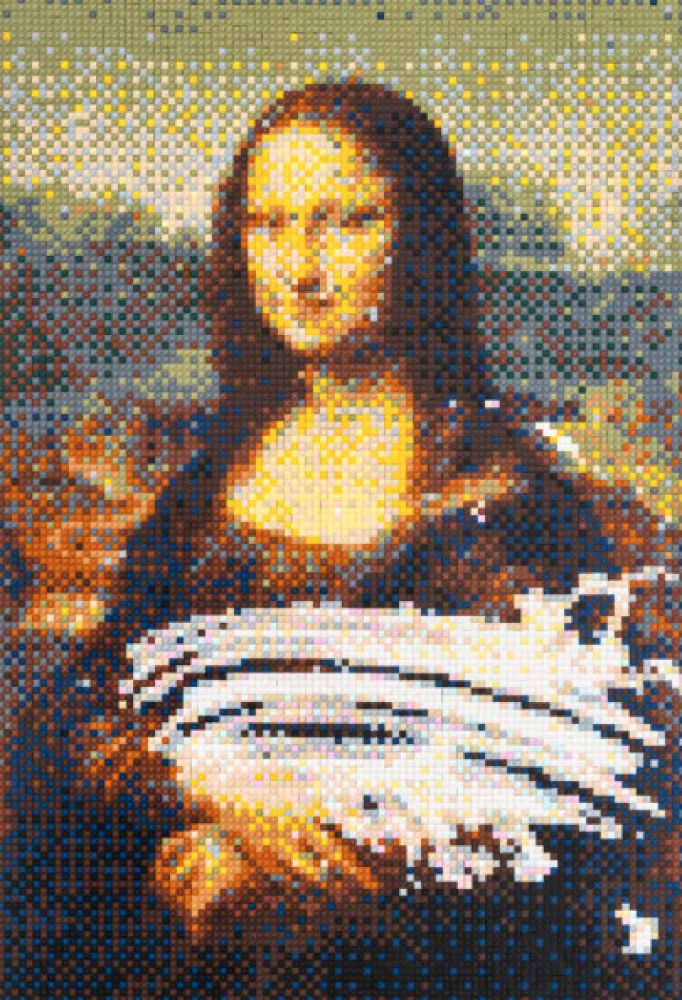

You have interpreted some of the great works of Western art history, particularly the Italian cannon, which may be seen as a provocation, but your work is never just a copy, there’s always an insertion. In The Last Supper Lego painting, why did you put yourself in the picture as Judas?

Actually, I have a little story about why I did this painting. When I was very young, I read a poem written by my father when he was in jail during the 1930s, sentenced for six years. He wrote about the moment when Jesus became a sacrifice, who betrayed him and all those stories of enlightenment. He told me that Judas sold some information and betrayed Jesus for a small amount of money, and put pressure on religion. His betrayal made Jesus become Jesus because of his sacrifice. I think that this is a very funny story because for me, a story needs someone like this. So I put myself as Judas because I want to tell people not to trust me.

In your Galleria Continua exhibition, you added a coat hanger in Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus in reference to brutal, self-induced abortions before they became legalised, while a panda appears holding on to a horse in Rubens’s The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus as a symbol of contemporary Chinese state power. You treat the coat hanger, panda and art history as readymade objects in a very Duchampian way. What’s the trigger for your works? Did you start by thinking that you want to express your concerns around abortion and women’s rights, or did these things just morph out of the process of found objects and what those objects might tell us?

My political position is never clear. That’s why the exhibition title Neither Nor. I’m not defending any rights except freedom of speech, which I think is an essential human right. Humans have the right to speak out. Freedom of speech means you’re not just saying the right thing; it gives you the possibility to say something wrong or that can be called wrong, so you can have a debate. If you don’t allow this kind of so-called wrong, then you’re in a most dangerous society.

What are your thoughts on the contemporary art world?

The so-called art world is absolutely disappointing, if there’s even an art world. When we talk about religion, we clearly know what religion is, but when we talk about the art world, if you had some art education, did some art theory, play with certain shapes, forms and style, then you can be called an artist, and the competition is basically business and financial. It doesn’t really have to do with how good the art is or what the essential meaning of art is, far from it. The art world is the most corrupt in the world, and I’m a part of it, so I should feel ashamed.

You feel that all or most politicians are dishonest, and politics is not something you’re interested in doing, but you feel that you must critique and comment on the world. However, the problems in society can’t all be the fault of politicians and somebody has to lead us, so what’s the solution? How do we change the system?

I don’t think human society can ever change for the better. We have been through so much and we are still living in such a primitive condition, making stupid arguments, becoming very shy about defending human rights and human dignity. Politicians all know that because we are all human, we cannot kill children, we cannot kill women, we cannot destroy a race or a city, but we’re doing it every day, and we’re going to do it in the future. We have so many bombs, we have so much military production, we are selling weapons and we profit from that, so are we going to really change it? It’s not going to be better. Nobody changes. People all know it’s wrong, but what can we do? The only thing that changes is that we will all die one day, but the next generation is facing the same shit.

Also see: The brat summer trend led by Charli XCX