6 Rising Chinese Artists You Need to Know

Jun 30, 2016

In the past decade, artists such as Ai Weiwei and Zeng Fanzhi have put China at the centre of the global art map. The onrush of the Chinese art movement that propelled them to international fame was quite sudden.

In the 1,500 or so years until the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Chinese art hardly evolved at all. Traditional shan shui paintings – depicting landscapes of mountains and rivers, or perhaps a galloping horse – were created using water and ink on paper. Calligraphy, another classical artistic pursuit, used the same materials to write poetry in flamboyant Chinese characters.

That all changed in the 1950s, when the Communist Party of China began encouraging artists to use Soviet-style socialist realism in propaganda posters extolling the virtues of Chairman Mao Zedong’s campaigns, which culminated in the Cultural Revolution. A liberal awakening in the arts followed Mao’s death in 1976, and an avant-garde movement came together.

Students in Beijing formed a group called the Stars. These young artists were born shortly after Mao came to power and had grown up with few freedoms. With Mao’s death, they felt the new China had endless possibilities.

“During the Cultural Revolution you could talk about the stars, but you couldn’t talk about them in public, because the stars did not exist,” says one of the founders of the Stars, Huang Rui. “The stars did not exist because there was only one sun, and that sun was Chairman Mao. The sun was the only thing that shone. Chairman Mao was the only one who gave light. The name, the Stars, seemed a very natural choice at the time.”

Influenced by the Western masters they were increasingly exposed to, the Stars found new freedom to paint everyday street scenes. One painting that hangs in Huang’s home depicts women sewing together. They are making bright, colourful clothes instead of the drab Mao suits they had long been made to wear. Such new-found freedoms were represented in the art produced as the Stars experimented with Western styles of painting and abstraction, abandoning the imagery of propaganda.

During the increasingly liberal 1980s, avant-garde artists exhibited paintings and sculptures and engaged in performance art in public places and private homes. The mainland had no galleries. But the growth in their popularity meant they could exhibit in the National Art Museum of China in 1989, before the political crackdown in June that year drove many abroad or into hiding.

By the mid-1990s another generation of artists had emerged. These artists focused more on painting and reflecting on the clash they were witnessing between communism and capitalism. Artists such as Wang Guangyi painted in a socialist realist style but, instead of communist slogans, Wang’s paintings were emblazoned with the brand names of Western watches, cars and drinks. Artists such as Fang Lijun and Zeng Fanzhi made large paintings of characters wearing masks and fixed, inane grins – hiding their feelings about what they had witnessed in their youth.

This second generation of artists rose to prominence as China opened up to the outside world. Western curators, museum directors and gallery owners visiting China loved the bright pop-art colours, the Western-style oil paintings and the references to China’s turbulent past.

In the 2000s, as China joined the World Trade Organisation and later invited the world to watch the most extravagant Olympic Games ever held, the prices of works by these second-generation artists rose sky-high. Museums scrambled to buy their output, and records were broken in auction houses around the world.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, the world was a different place. A third generation of modern Chinese artists emerged. These artists were born after the death of Mao. They grew up in one-child families in an increasingly prosperous China. The politics their predecessors were immersed in was just background to these globalised youngsters. The environment, social problems and the global recession were more important to them than Mao’s Little Red Book or the Cold War.

This generation creates global art for a global audience, and identity is more important that nationality.

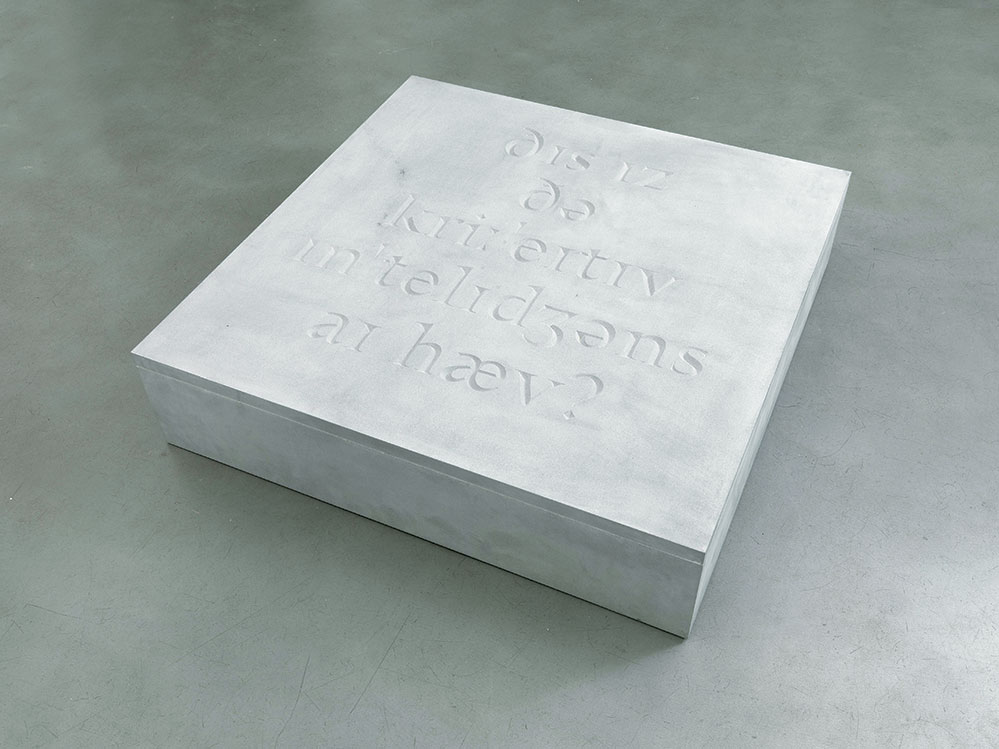

Kong Lingnan (Born 1983)

Kong Lingnan came to prominence in 2011, when she exhibited at Beijing’s prestigious Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. The show, entitled Only Her Body, was curated by an older, established artist, Yang Shaobin. The works sold out before the opening, bought by big-name collectors such as Baron Guy Ullens de Schooten.

It’s easy to see why her paintings are popular. Kong paints on glossy blacked-out canvases, in a style that make her works look like lit neon. The electric blues, pinks and yellows appear to emit light, glowing against their dark backgrounds. “I’m intrigued by neon,” she says. “It has a particular beauty and loneliness that is very similar to the world we live in.”

Kong’s early series shows dark scenes of arctic mountains, with pink oil spills, luminous crashed planes, whalers in action with their harpoons, and radiant blue submarines cracking through electric white ice. The heat of the neon lines gives an unsettling impression of toxicity and erosion of the icy landscapes.

Her follow-up series depicts lonely individuals and couples, some watching planes exploding, others lost at sea, yet others drowned, washed up on the banks of a lake. The paintings are isolating, harrowing and shocking, yet startlingly tranquil and calming.

They are meant to be so. “My works are related to society and the environment, but there is no beauty or ugliness, no right or wrong, no good or evil,” Kong says. “The world simply exists, and this is all we know.” The pollution, destruction and moral erosion of the planet are things we are walking into with our eyes wide open.

Is enough being done? Is it even being discussed? The questions are being asked by the younger generation. Pollution can be seen everywhere in China, yet the dirt, smog and putridity of the water are not glamorous matters to take up. Kong’s clean lines and glossy imagery manage to give pollution an elegance, leaving it to speak for itself.

Her more recent work shows dots of light on her trademark dark background. At first glance, they look like stars in a faraway galaxy. But the images are of the Seychelles and other groups of islands, taken from Google Earth. The sea is rising and islands shrinking because the polar ice caps are melting.

Kong studied at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. The flickering signs of the restaurants and bars that she could see from her studio window inspired her to use a neon style to enable her messages to jump out from the dark. The artist has since moved away from the back streets of Beijing, collaborating with owners of brands, including the Vogue brand, which have shown her art works and installations at conspicuous events. Her unique style and subject matter may well draw the attention of the greater art world to her like moths to neon lights.

Huang Ran (Born 1982)

Huang Ran’s darkly humorous works are created in a wide range of media, including painting, photography, video and installations. The underlying themes that permeate his work are brainwashing and manipulation, power and influence.

Huang was born in the western Chinese province of Sichuan, but moved to Britain in 2002 and graduated from Goldsmiths, a college of the University of London, in 2007. “I went straight from rural Sichuan to London,” he says. “At that time it was very hard to get access to information in China, so I didn’t know what I was getting into. I was a blank piece of paper.” The idea of discovery influences much of Huang’s work. Humans, he says, are made up of a series of encounters: the books we read, the people we meet, each leaves its mark, meaning we are, in essence, stealing other people’s experiences. “After this conversation, maybe I will steal something from you, and you will steal something from me,” he says. “It’s how we build up experience.”

Huang believes there is no true singular history unless it is lived by the individual, as each person’s version of a moment is distorted as it is retold. Memories are manipulated and truths are misappropriated. The Administration of Glory is a 30-minute film, made by Huang in 2014, which focuses on the notion of theft. It follows various interlinked thefts: an office worker steals an ancient sword, masked men steal the office worker’s car, a diner steals his neighbour’s wine and a scientist tells of his life’s work, brainwashing a boy. The film was nominated for the Short Film Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

The Administration of Glory was shown recently as part of Huang’s solo exhibition at the Simon Lee Gallery in London. Another part of the exhibition was a revolving billboard bearing the words: “They believe this is history because…they believe this is history because…”

Huang wishes us to question the histories we learn at school and from others. He finds it hard to imagine a tale that can be anything other than unique to the teller. “What if I really experienced this history myself, how would I have understood these things?” he says. Huang’s paintings are like his videos in that he often copies the

works of other artists. For example, he nearly replicates paintings by German artist Martin Kippenberger, but adds elements of banality, humour and sarcasm – imparting his own ego, just as an actor puts his own personality into the character he plays.

Paintings by Huang depict heroes in their own worlds, setting records in pursuits as pointless as striving to make the biggest ball of paint, to develop the biggest biceps, to eat the most hot dogs, to assume the stupidest name. The achievements of these heroes become monumental feats through being recorded in the public domain for the whole world to see. “I am trying to capture these small irrelevant things, and by doing so make them important. I want to ask, what if history had been written this way?”

Jia Aili (Born 1979)

Jia Aili has risen to prominence as one of the youngest of the latest generation of Chinese artists. He earned a degree in painting in oils from the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts in the northern Chinese city of Shenyang in 2004, before moving to Beijing.

Jia’s education and his understanding of Western Old Masters can be seen clearly in his work, but the subject matter is the social and economic climate of 21st-century China. Many of his chilling works depict great masses of sea or land: frozen tundra, or perhaps post- apocalyptic landscapes with lost individuals wearing space suits or gas masks.

Jia was born in Dandong, on China’s border with North Korea, a city ravaged many times in China’s wars with Japan and the United States. As a child, Jia watched the city grow along with China’s weapons and space rogrammes, and saw the effects of industrialisation and the pollution that followed.

The artist was born the year after China’s one-child policy was introduced. So he grew up observing all by himself the changes his country was undergoing. His works convey this isolation, many with solo figures scanning the desolate landscapes.

Jia’s work encompasses the advent of new technology and new applications of science, but also the effects of disease and war. It covers the substitution of economic growth and development for beliefs, religion and tradition. It shows the disharmony between mankind and nature, and the sacrificing of utopia in the name of industrialisation. “There are endless unresolved social issues in our society, as the root of these problems is ingrained in our society,” he says.

Wide open landscapes spread away into the distance in Jia’s paintings, just as they do in Renaissance paintings. But in Jia’s world an industrial wasteland and polluted rivers fill the foreground as young observers in gas masks watch space rockets blast off in the distance.

He is sufficiently accomplished as a figurative artist to make clear that the observers in his paintings are lost in thought as they contemplate the disasters unfolding around them.

The observers, and the paintings they populate, are melancholy and lonely. Jia argues that the better connected people become, the more lonely they become.

“My work usually explores themes of realism and depicts the current situation of life,” he says. “I create images in reference to what’s happening now. Whilst realism was how I started painting, now narrative is more prominent in my works.”

Certainly the market has taken note. Two years ago, Sotheby’s sold one of his works for HK$7.4 million, making Jia one of the youngest of the Chinese artists now working to become a US dollar millionaire.

Wang Guangle (Born 1976)

Wang Guangle’s graduation show at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing was entitled 3pm to 5pm. The title refers to the period when light streams into his studio, cutting across the floor. His interest in light is apparent in many of his paintings, which seem to have a glow of their own.

By slowly diluting one pot of paint in another, the gradual changes in tone as Wang dips his brush and then layers the canvas, over and over again, produce an aura that seems three-dimensional. For his installations, he applies layers of paper and paint to a wall until they do, in fact, become three dimensional, so the wall reaches out to the viewer.

Wang’s early works concentrated on colour and line, with bright, bold colours strafing the canvas. The latest series is more calming, with subtle tones pulsating out of the canvas. His vast paintings of tiny stones, rendered in minute detail, can take more than a year to complete. The works reflect the timelessness of the subjects – stones having always been appreciated by learned Chinese – and the time it takes to paint them.

“There is so much focus on the development of the country, the changes in society, the impact of history, but art is just a shadow of these things,” Wang says. “My work isn’t a reaction against this fast pace of change, but reflects my personal relationship with time.”

Having remained in the same scruffy studio in a village outside Beijing for over a decade, he persists with his pursuit, regardless of what’s happening outside his door.

Unlike the work of older artists, whose subject matter is as changeable as the society they live in, Wang’s work maintains a steady pace, humming in the background like white noise. “No matter where you are, or what your style is, the one thing we all have in common is time,” the artist says. “Time always marches on, whether you like it or not.”

Tu Hongtao (Born 1976)

After graduating from the China Academy of Art in the eastern city of Hangzhou, Tu Hongtao moved first to Guangzhou in the south and then Chongqing in the southwest, to work as an artist and – so he could afford to live in the big city – as a seller of clothing. The works he did between 2004 and 2008 reflect the tension, the violence and the crowds in the cities he lived in.

In these works, buildings crammed together form the backdrop to semi-naked women piled up against each other like toys. The titles, such as Maybe Tokyo or Chengdu, are a reference to how big cities and the people that live in them lose their identities and become like one another. “As an outsider, someone who had just landed in this community, I was completely overwhelmed,” Tu says. His intense works evince a claustrophobic atmosphere where everything is for sale, even people.

After the economic downturn of 2008, Tu decided to move his studio to a tranquil community of artists near his home town, Chengdu. His studio sits amid an archetypal vision of rural China, complete with a lake filled with lilies, bamboo forests and lush greenery – all visible from his window. His works today focus on the natural landscape he is ensconced in.

“This new environment helped shift my attitude and my working style to a new, more optimistic outlook,” Tu says. “I grew up at a time where there was a spiritual and material conflict of interest. People were desperate in their pursuit of material positions, which led to an erosion of society.”

Chinese traditional culture is at the root of Tu’s work, but his study of Western culture gives him a new viewpoint. On visits to Europe to meet artists such as Daniel Richter, he learned more about art abroad, giving him more scope to understand fully his own work. “Western abstract art is based on representation of the physical perspective and then the deconstruction of this,” he says. “However, Chinese painting has always had an innate abstract sense. Traditional Chinese landscape paintings show this through their use of single lines and blank space.”

Tu’s subject matter is the natural environment, but his works are anything but natural. Reality is distorted as elements of the landscape that excite him are emphasised, focused on and reworked, to create dark, thickly painted areas. Areas he finds of no interest may well be left empty, leaving the canvas blank.

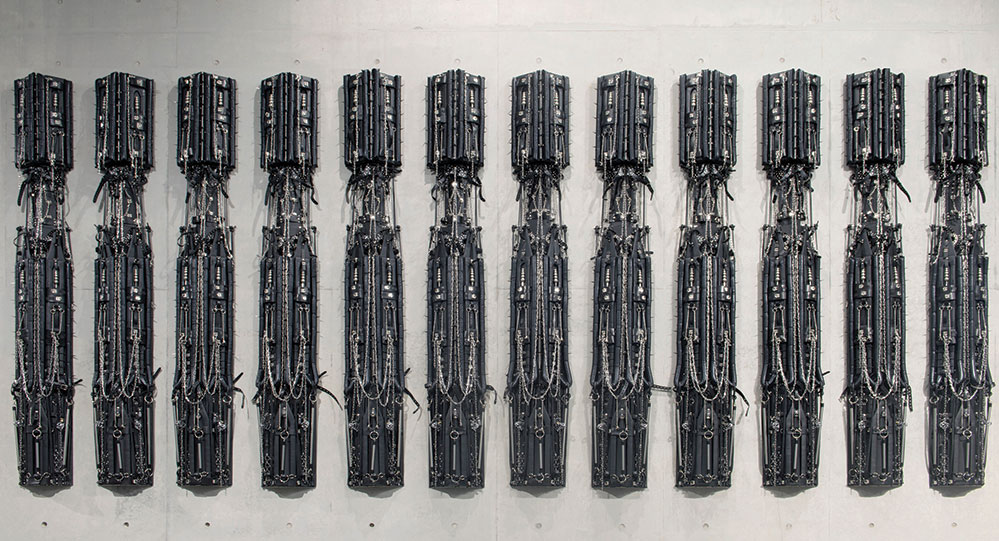

Xu Zhen (Born 1977)

Xu Zhen is a conceptual artist and key figure of the Shanghai art scene, who creates sculptures, videos and installations that break bounds set by society and deal with taboos. He confronts sexual, political, and social issues that confuse, confound and often shock the viewer of his art. His works look at the mundane aspects of urban life and use humour to deal with serious topics intelligently.

As a leading member of the latest generation of Chinese artists, Xu was the youngest ever to have his work shown at the main thematic exhibition of the Venice Biennale, and his works are shown at important museums and art fairs around the world.

Xu’s 2007 installation, ShangART Supermarket, recreated an entire shop inside the gallery, but with only empty packaging on the shelves. It is one of several works he has done that deal with the emptiness of art world and that question the financial value of art. In 2008 he put on The Starving of Sudan in the Long March Space in Beijing, where he recreated Kevin Carter’s photograph of a baby in Sudan being stalked by a vulture. The vulture in the art work was stuffed, but the baby was real, and this caused mixed feelings among the viewers, whom the exhibition put in the position of the photographer.

Bondage equipment is another source of material for Xu’s works. The five-metre-long cathedral he recently created was made entirely out of handcuffs, collars, gags and other such paraphernalia. The work, entitled Play 201301, is a reflection of the power of sex and the Catholic Church’s attitude to it. “Part of the challenge when creating this huge installation was to confront the idea of concealment, hypocrisy and silence,” Xu says.